The Basketball FROGs

The players who define greatness in basketball — including a doctor who made house calls

Everyone talks about the Greatest of All Time. The GOATs. That’s fine. I want a wider lens. And that’s why I’m introducing the FROGS.

FROG stands for Flagship Representative of Greatness.

I like to think of FROGs as Knights of the Round Table of sport, the people who expand the definition of greatness.

I put up a poll asking readers to name one GOAT in various sports. I have used those results, opinions from various people around the sports world, and my own judgment to name the FROGS. It’s important to say: These are just the opening list. We will add more players as time goes on.

Our first collection of FROGs came from golf. They included:

Tiger Woods

Jack Nicklaus

Arnold Palmer

Ben Hogan

Bobby Jones

Today, we turn to basketball — and we have a special guest to introduce one of our FROGS. Let’s go!

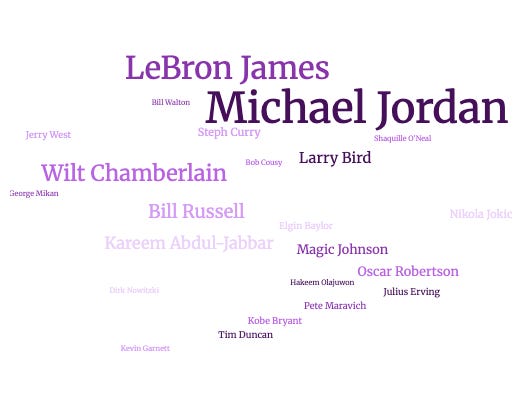

OK, as usual, the first thing we do is show you a word cloud of your top choices for the greatest player of all time. As you might expect, Michael Jordan and LeBron James lead the conversation — with Jordan comfortably ahead. Wilt Chamberlain is the clear third choice ahead of Bill Russell.

I can’t say I’m surprised by any of that. The Jordan-LeBron GOAT argument has grown tiresome to me, mainly because I don’t think anybody is changing their mind. It seems to me that the whole GOAT concept builds around the idea that we grow up believing someone is the greatest ever … and someone extraordinary has to come along to knock that person out of the top spot.

That’s where the conversation begins and ends.

For instance, I grew up believing that Wilt Chamberlain was the greatest. He had to be, right? He scored 100 points in a game. He averaged 50 points per game for a whole season. I never saw Wilt play, but those numbers so boggled my 10- and 12-year-old mind that I instinctively had him at the top of the game, along with others I never saw play like Babe Ruth and Jim Brown.

Then I saw Jordan. Our family moved to North Carolina when he was a freshman at UNC, and I had chosen the Tar Heels as my team in order to fit in, and I sort of met him when he was a junior (in an autograph crush by his car, he turned to me and said “Sorry kid, I gotta go!”), and then the dunk contest and the 63-point game against the Celtics, and the shot over my guy Craig Ehlo, and the championships, and the odd baseball turn, and then the incredible shot over the Utah Jazz that Margo and I watched while on our honeymoon — I simply could not imagine anyone, not even Wilt, playing basketball better than Michael Jordan.

My heart will always say Jordan.

My head will say LeBron because he’s bigger and stronger and a better passer and a better rebounder, and he gave me the only Cleveland championship of my lifetime.

My head will probably someday say Wemby because he’s MUCH bigger, and you can’t shoot over him, and he’s a 100-foot sequoia who makes three-pointers, and he might just break basketball as we know it.

My heart will always say Jordan.

Just as your heart might always say Wilt. Or Russell. Or Oscar Robertson. Or Nikola Jokić. Or whoever was the basketball star who first filled your imagination.

Like I say, that’s where the conversation begins and ends — a debate between the head and the heart. So we’re expanding that conversation and talking FROGs instead, the Flagship Representatives of Greatness, the knights who made basketball what it is.

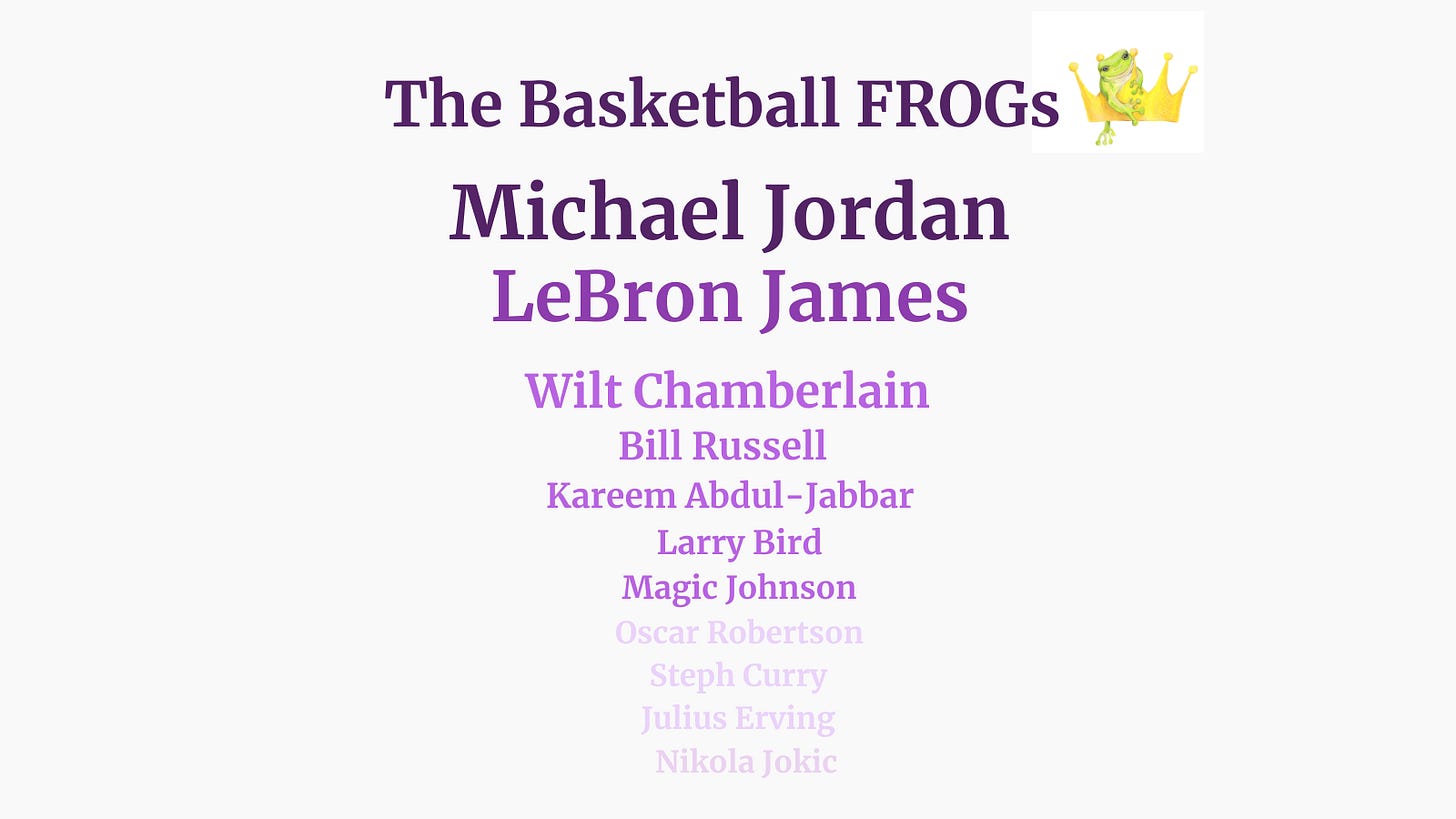

Here is the first class of basketball FROGs — there are 11 of them.

Julius Erving: The Soul of the Street Game

For each list, I’m going to try to find a guest to write the lead essay. This one was easy — Luke Epplin’s wonderful new book, Moses and the Doctor: Two Men, One Championship, and the Birth of Modern Basketball comes out today. I can’t recommend it more highly, and I asked Luke to write a little something about what made Julius Erving so special — and a FROG.

From the moment he surfaced on the national stage as a sinewy, scarcely known forward from the University of Massachusetts, his Afro flared high and the American Basketball Association’s distinctive red-white-and-blue ball swallowed up by his enormous hands, Julius Erving appeared a vision of the future, an avatar of a sport that was shifting from the ground to the air. Like compatible puzzle pieces, the ABA and Erving locked into place at once. One was a fledgling start-up scrambling to disrupt the National Basketball Association’s hold on the sport’s top talent, the other a leaper from Long Island who’d amassed a cult following on the asphalt courts of New York City.

Erving carried that playground sensibility into the ABA, complete with an alter ego, Dr. J, whose balletic moves defied belief. The ball cupped in one hand, his body contorted yet controlled, he spun in physics-defying shots that NBA legend Bill Russell deemed “beautiful in the way that an ice skater’s leap is beautiful—or even in the same way that a painting is beautiful.” More than anyone else, Erving injected the playground into the bloodstream of professional basketball, legitimizing moves that old-school coaches used to bench players for attempting. “My overall goal,” Erving once stated, “is to give people the feeling that they are being entertained by an artist—and to win. You know, the playground game, refined.”

It was this merger between artistry and dominance, improvisation and command, flair and fundamentals, that elevated Erving into a folk legend. For the first five years of his career, during which he clinched two championships for the New York Nets, Erving was the ghost in the machinery of professional basketball, more rumor than reality in the untelevised ABA. His crossover into the NBA in 1976 proved that the hype hadn’t been overblown. Over the following seven years, he won an MVP, advanced to the NBA Finals four times, and romped to a championship in 1983 alongside Moses Malone, whose “Fo’ Fo’ Fo’” prophecy nearly came to pass.

An entire generation of acolytes came of age copying Erving’s moves on the playground, Michael Jordan chief among them. They burst into the NBA crafted in Erving’s image: creative, entrepreneurial, impervious to gravity, and with style to spare. His freewheeling, expressive spirit on the court came to define basketball across the globe. Off the court, too, Erving left a lasting legacy. In the late 1970s, Erving buoyed the NBA by serving as an ambassador for the sport, an accessible and dignified figure who counterbalanced the scandals and drug problems that marred the league. It was enough for Kevin Loughery, his former head coach with the New York Nets, to assert upon Erving’s retirement in 1987 that “Doc has done as much for basketball as any other player in the whole history of the game.”

The First Class of Basketball FROGs

All FROGs have an equal seat at the round table. This list isn’t ranked, but it is ordered. Somebody has to be Lancelot.

Michael Jordan: He could fly. And he had to win.

LeBron James: Total basketball. The game bent to his will.

Wilt Chamberlain: Limitless force of nature.

Bill Russell: Winning as an art form.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Longevity, intellect, an unblockable shot.

Larry Bird: “So, who’s coming in second?”

Magic Johnson: Didn’t invent the fastbreak. But reinvented it.

Oscar Robertson: Stockpiled triple-doubles before they were a thing.

Steph Curry: Redrew the lines, altered the geometry of the game.

Julius Erving: Virtuoso in mid-air.

Nikola Jokić: Unparalleled genius hidden in Cookie Monster’s body.

I mean, people only think LeBron is better than Jordan because he's bigger, faster, a better shooter and passer and rebounder. And played more games. It's really unfair to compare them.

It's like comparing a 10-pound bowling ball to an 11-pound bowling ball and trying to figure out which one weighs more. It's not something we can ever settle definitively.

The peak of Shaq is the greatest player of all time. It didn’t last that long 2000-2006 but to me it’s the best ever