Today, the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Shohei Ohtani and the New York Yankees’ Aaron Judge will win the National League and American League Most Valuable Player awards. This isn’t a spoiler. The outcome is certain.

What’s also certain is this: Baseball’s biggest annual award—probably the biggest annual professional award in all of sports—will not be revealed in a Hollywood ballroom or a Las Vegas theater.

No. It will be revealed in the MLB Network studio in Secaucus, N.J.

The award will not be handed out by Tom Hanks, or Jon Hamm, or Jennifer Lawrence, or some gigantic movie or television star in front of a gallery of celebrities. There will be no envelope, no music, no hype, no tributes, no over-the-top awards extravaganza.

Nope. The MVP will be divulged on a Thursday evening in front of a handful of producers and camera people and a television audience likely no larger than a midweek afternoon game at Dodger Stadium. The winner will probably be at home, in their living room, with their spouse or a pet or both.

This is baseball’s legendary, baffling, groundbreaking, controversial, marvelous, frustrating, and just plain weird Most Valuable Player Award.

And this is how we got here.

We start with the word. Valuable.

No single word—with the possible exception of “Bonds”—has been at the center of more baseball arguments through the years than “valuable.” Skirmishes have broken out on the sliver of land between “valuable” and “important.” Full-scale wars have been fought on the postage-sized territory between “most valuable player” and “best player.”

Yes, baseball fans will go all Charles Merriam AND Noah Webster on you when the fight turns to what “valuable” really means.

Of course, it’s just a word… and like most baseball words, it has a pretty easy-to-follow origin story. Pitchers are called pitchers because, in the early days, by rule, they had to pitch the ball underhand. Clubhouses are called clubhouses because, in the early days, baseball teams were social clubs and the players/members spent their time before and after games in an actual clubhouse.

When people in those same early days talked about baseball players being “valuable,” they were referring to specifically how much money it would cost to get them to play for the team. The “most valuable” player was the one who cost the most. The original Most Valuable Player—at least the first public MVP—was a defensive whiz named George Wright, who was paid $1,400 to play for the first openly professional baseball team, the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings.

It was quite common, in the years before 1911, for sports writers and baseball fans to muse about which player was, indeed, the most valuable, and thus worth the most money. But there was no shape to it, no form. There were countless trophies, loving cups, buttons, watches, pins, pens, plaques, certificates and such awarded to baseball players in those years, but they were almost universally tied to one specific aspect of the game—fielding or batting average or pitching prowess or stolen bases or something like that.

The idea of giving out an award to the most valuable player must have seemed an utterly bizarre idea to those early baseball fans. After all, the Most Valuable Player, by definition, already got the Most Valuable Prize.

You know. Money.

So, what changed?

Well, it all stars with a remarkable character named Hugh Chalmers.

Hugh Chalmers was a natural-born salesman. When he was 14 years old, while working as an office gopher for the National Cash Register company, he sold his first cash register. The feeling intoxicated him.

So he just kept on selling cash registers. He was relentless. He sold with an enthusiasm and energy that simply overwhelmed people. “Salesmanship,” he used to say, “is nothing more nor less than making the other fellow feel as you do about what you have to sell.”

Customers would have sworn that Hugh Chalmers’ great passion in life was cash registers, that he spent every waking hour thinking about them. Chalmers’ wanted them to feel that way. But his passion was not cash registers at all. It was the sale.

“It doesn’t make any difference whether we are trying to sell a house and lot or a paper of pins,” he said.

At 35, he decided it was time to run his own company. He chose the car business. He had no more personal attachment to automobiles than he did cash registers—he had actually never driven a car in his life—but he sensed that America was about to go car crazy. He sensed this in 1908, the very year that Henry Ford began mass producing the Motel T. So, you know, pretty good prediction.

Chalmers started the Chalmers-Detroit Motor Company and built it around two principles: (1) Salesmanship, of course. (2) Advertising… which he defined as “salesmanship plus publicity.” He was a zealot for both.

“All the best inventions in the world would have fallen flat had it not been for advertising and salesmanship,” he said. “Therefore, I think it will not be stating the case too strongly to say that advertising and salesmanship have done more to push the world ahead than anything else.”

Chalmers advertised his cars as both the best in quality while still being affordable.

And a personal favorite …

He advertised in newspapers, in magazines, on billboards, in the previews before moving pictures, obviously, but he wanted to find new frontiers to reach potential car buyers. It was only a matter of time before he got to baseball. Chalmers was an incurable fan, particularly of the Detroit Tigers, who in 1909 shocked everybody and won the American League pennant. He was particularly a fan of the team’s manager, Hughie Jennings, and the team’s ferocious young star, 22-year-old outfielder Ty Cobb.

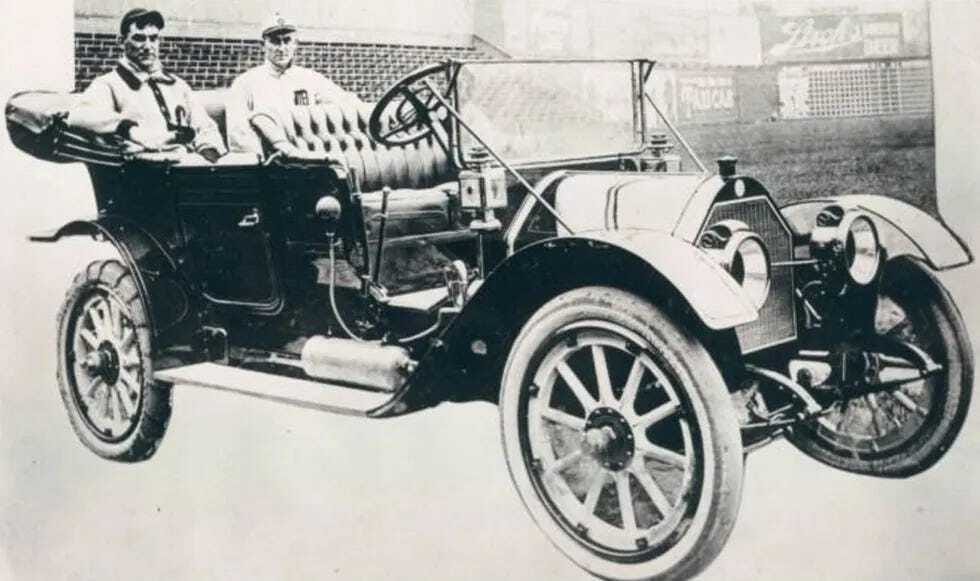

After the Tigers lost to Pittsburgh in the World Series, Chalmers approached the presidents of the American and National League and made an unprecedented offer: He wanted to give an automobile to the winner of the major league batting title.

And… he was not giving away just any car: He wanted to give away his jewel, a Chalmers Model 30 Roadster with 30 horsepower, the car he understatedly called “The envy of the world!”

It was a stunning proposition. The Roadster had a sticker price of $2,000… which was roughly what the St. Louis Browns were paying for their entire roster. But Chalmers knew exactly what he was doing. He knew that the story would be irresistible to players and fans alike.

“The offer of an automobile is awakening a lot more enthusiasm among both players and fans than any trophy which could be offered,” Cobb said. “I would much rather win an automobile than any other prize.”

“A motor car for the leading batsman,” said Honus Wagner, widely viewed as Cobb’s greatest competition for the Roadster, “has the usual medals and loving cup beaten by a mile!”

“As usual,” Cobb’s teammate Wahoo Sam Crawford said, “Chalmers is in the lead with a great offer of something worth striving for. I own a Chalmers car already, and so I know just how good a prize is in store for the season’s leading hitter.”

Now, it should be said that this was not an MVP award. We are only at the start of our story. Chalmers was following the well-worn path of giving a prize—albeit a much higher-level prize—to the “leading batsman.”

Chalmers was thrilled by the rollout. The story was in all the papers. Sportswriters gushed that the 1910 race for the batting championship would be unlike any before. He had felt sure that the publicity the Chalmers Company would receive would be worth many multiples of the car price. He was right.

He just had no idea what a pain in the neck he had created for himself.

One thing baseball fans do not appreciate enough, I think, is just how thoroughly gambling and baseball intersected in the early days of baseball. Everybody knows about the Black Sox, the Chicago club of Shoeless Joe and Eddie Cicotte and Chick Gandil and the rest who consorted with gamblers and threw the 1919 World Series. Many seem to think that was a one-of-a-kind anomaly.

It was not. The story of fixed baseball games goes back to at least 1865, which is four years before the Cincinnati Red Stockings even became baseball’s first openly professional team. There’s no telling how many baseball games were thrown through the years, but just in the years leading up to the Black Sox:

Connie Mack suspected that his Athletics threw the 1914 World Series; they were heavy favorites and got swept in four straight by the Miracle Braves.

The New York Giants’ Heinie Zimmerman—who would later be given a lifetime ban for fixing games—was strongly suspected of helping throw the 1917 World Series, ironically against the Chicago White Sox.

Many believe that the Chicago Cubs threw the 1918 World Series to the Boston Red Sox. In fact, Eddie Cicotte—perhaps the key figure in the Black Sox scandal—said in court that it was an open secret that the Cubs players were offered $10,000 by gamblers to fix the Series.

Ty Cobb, among others, threw a game in 1919 and several players bet on it, including possibly Cobb.

Hugh Chalmers undoubtedly didn’t think even consider that gamblers might get their hooks into his wholesome car giveaway. But by turning the 1910 major league batting race into a national spectacle, he was unwittingly guaranteeing it.

As the season headed into its big finish, Cobb and Nap Lajoie were locked in a batting race that was, quite literally, too close to call. In those days, statistics were kept haphazardly. The league offices did not release the official numbers until weeks after the season was over. As such, every paper in the country seemed to have different batting averages for the players. Almost all of them had Cobb ahead going into the final day, but by how much? Nobody knew!

But everybody cared! The story was mesmerizing. The characters were eternal. Lajoie was a living legend who had, almost singlehandedly, created the American League with his star power. Cobb was a brash young slasher who was already being touted as the best of them all. On the last day, Lajoie’s Cleveland team—named the Naps in his honor— played a doubleheader against the sad-sack St. Louis Browns. Reporters had no idea how many hits Lajoie would need to overtake Cobb. They surmised that he would need a lot.

And… Lajoie got a lot of hits. In all, he was credited with going 8 for 8. It might have been one of the greatest performances in baseball history—think of it! He went 8 for 8 on the final day to win the car!—except for a handful of inconvenient facts:

One of the eight hits was, by contemporary accounts, a routine fly ball that an outfielder comically misjudged.

The other seven hits were all bunt singles—by a 35-year-old man who was never that fast, even in his youth. These singles were made possible by a rookie third baseman who was ordered to man his position in leftfield.

Lajoie also had a bunt that was ruled a sacrifice. The St. Louis Browns’ coaches attempted to bribe the official scorer to rule that a hit, too.

The Browns had not only thrown the batting title to Nap Lajoie… they had done so in the least convincing manner imaginable. Nobody was fooled.

“In ‘Fixed’ Game Browns Loaf and Let Larry Win,” was the headline in The St. Louis Star and Times.

“ST. LOUIS LAID DOWN TO LET LAJOIE WIN,” roared the Richmond Times-Dispatch headline.

“Race tracks were closed for less than this,” sports editor H.W. Lanigan wrote.

“Never before in the history of baseball,” The Washington Post wrote, “has the integrity of the game been questioned as it was by the 8,000 fans this afternoon.”

Why did the Browns throw the batting title to Lajoie? For many years, the given reason was that they just hated Cobb that much. Cobb was, indeed, disliked by a lot of players, but it isn’t actually clear that the Browns had any specific beef with him. Anyway, even if they did hate him… they certainly didn’t give Lajoie eight hits and try to bribe the official scorer and make a mockery of the game (fans booed relentlessly) out of sheer spite for Cobb.

No, this is surely a gambling story, and it’s one of the most shameful days in baseball history.

It only got worse. The American League president in 1910 was also the league founder: Ban Johnson. His singular purpose in life was to protect and grow his American League. When he saw what happened, he instantly knew that there was an existential danger at play. He had to do something, or the entire validity of the batting race and his league would be in question.

He promptly made two announcements:

He would thoroughly investigate what happened in St. Louis.

There would be no more individual awards given out while he was president of the American League. He said: “The merest suspicion of crookedness work irreparable injury to the game, and from now on, no more individual contests for prizes will be allowed.”

Our focus is on the MVP award, but just to tie a bow on the Lajoie saga: Ban Johnson obviously did not do a thorough investigation. What he did do was announce that all of Lajoie’s hits were kosher while he quietly banished the Browns’ officials who tried to bribe the scorer. Then, in an audacious bit of bookkeeping, he found two extra hits in Ty Cobb’s season. Those two phantom hits gave Cobb the batting title.

It was two hits only because Cobb didn’t need three.

Perhaps the most remarkable part of this story is that Hugh Chalmers didn’t just quit on baseball right then and there. His simple and elegant idea of giving a car to the batting champion had turned sour, not only because of the corruption in the American League race—Chalmers ended up giving both Cobb and Lajoie cars—but also because he had to endure endless gripes from fans of Sherwood Magee, who had beaten out heavily favored Honus Wagner for the National League batting crown. True, Magee’s .331 average trailed Cobb and Lajoie by more than 50 points, but a title is a title, and Magee bitterly wondered why HE wasn’t getting a car, too.

There’s your reward for trying to work with baseball, Hugh Chalmers.

But Chalmers loved the game… and he loved the publicity. He still wanted to give away a car (now he was thinking of giving away two cars) to the best players. Ban Johnson and Detroit Tigers owner Frank Lavin, who had become a Johnson acolyte, were adamant that there be no more individual awards for players who led the league in an individual statistic. Chalmers needed a whole new approach.

Nine days before the 1911 season began, Chalmers announced that he would give away a Chalmers Model 35 Roadster—bigger and better than ever!—to a player in each league. But… this would be different.

“Heretofore,” he said in a statement, “trophies for baseball prowess have been given for superiority in some one department. There have been prizes for champion base stealers, for champion fielders, but chiefly for champion batsmen. The Chalmers trophies will be awarded for general ability.”

General ability? What did that even mean? Chalmers explained he would give a car to the player who “should prove himself as the most important and useful player to his club and the league at large in point of deportment and value of services rendered.”

Value of services rendered.

Hugh Chalmers had just created the Most Valuable Player Award.

Yes, I know, he also said, “most important and useful player”—he obviously thought all of that was pretty well synonymous—but the point is there had never been an award quite like this in American sports… or perhaps in sports anywhere in the world. This was not an award for statistical excellence. This was not an award that could be thrown by corrupt players. This was an award for the player judged to be the most valuable.

And who would do the judging? Well, it couldn’t be the players themselves. The owners could do the judging, but that would bring all sorts of troubling side issues. No, there was really only one group that could do it.

The voters had to be the baseball writers.

In that spirit, Chalmers hired his friend, a longtime baseball chronicler named Ren Mulford Jr., to put together a committee of his fellow sportswriters. Mulford, who had been around baseball since the Cincinnati Red Stockings started paying players, appointed 11 sportswriters, one from each of the big-league cities at the time.

John B. Foster, New York Telegram (Giants and Highlanders)

I.A. Sandborn, Chicago Tribune (Cubs and White Sox)

Tim Murnane, Boston Globe (Braves and Red Sox)

J.C. Isaminger, Philadelphia North American (Athletics and Phillies)

M.F. Parker, St. Louis Globe-Democrat (Browns and Cardinals)

Abe Yager, Brooklyn Eagle (Dodgers)

Jack Ryder, Cincinnati Enquirer (Reds)

H.P. Edwards, Cleveland Plain Dealer (Naps)

J.S. Smith, Detroit Journal (Tigers)

C. B. Power, Pittsburgh Gazette-Times (Pirates)

J.S. Jackson, Washington Post (Senators)

Chalmers, Mulford and Ban Johnson then came up with the ingenious MVP voting system that’s still in use today. Each sportswriter would rank, in order, the eight most valuable players in each league. When all the ballots were in, the winner of the car in each league would be the player with the most points—eight points for every first-place vote, seven points for every second-place vote, and so on down the line.

The 1911 battle for the Chalmers Trophy was baffling to people at first.

“Considerable misapprehension exists regarding the purpose and method of award of the Chalmers Trophies, which are given to the so-called ‘best players’ in each of the major leagues this fall,” a sportswriter wrote. “The new Chalmers Trophies are of an entirely different nature, the only resemblance being that they are motor cars. A high batting average will not entitle a player to the prize. In fact, it is wholly within the possibilities that the winner may have a low batting average with the bat.

“It was decided, instead, to offer a prize for the player who proved himself of most value in all departments of the game.”

On October 15, Chalmers showed up on a stormy day when the Cubs and White Sox were supposed to play Game 2 of the Chicago City Championship Series and awarded a Chalmers Trophy car to Cubs outfielder Frank “Wildfire” Schulte, who had led the league in home runs and RBIs. Schulte was a surprise pick; most people thought the award would go to Christy Mathewson.

This cartoon ran in the Chicago Tribune.

A couple days later, Chalmers showed up at World Series Game 3 to award the American League car to Ty Cobb, who won the Chalmers Trophy unanimously after hitting .419. Cobb was so dominant in 1911 that The Sporting News actually ran a glowing editorial saying that he should remove his name from consideration because nobody in baseball was in his league.

“This trophy,” Mulford said to Cobb, “is the greatest possible individual award that can be paid any ballplayer.”

Ty Cobb led the American League in hitting each of the next three seasons… but he never again won a Chalmers Award. This was a point of contention at the time—one St. Louis sportswriter called the award “an annual joke”—but with the benefit of hindsight and advanced statistics, we can say that the American League committee made defensible, even prescient choices every year. Tris Speaker led the league in home runs and on-base percentage in 1912, Walter Johnson had his legendary 1.14-ERA season in 1913, and Eddie Collins was terrific in 1914. All three, looking back, had more Wins Above Replacement than Cobb in their respective winning years.

The National League choices were a bit more baffling—Larry Doyle somehow won the 1912 award over Honus Wagner, Brooklyn’s Jake Daubert won the award over Gavvy Cravath in 1913, and Boston’s Johnny Evers over Pete Alexander in 1914 was ridiculous… but, hey, as we will see, controversial choices are another big part of the MVP’s hold on the attention of baseball fans.

Actually, let’s pause for just a minute on Gavvy Cravath. Daubert led the league with a .350 average in 1912 to win the award. Cravath hit nine points lower, but he led the league in home runs and RBIs.

A few years later, Cravath—in a piece ghost-written by F.C. Lane—went into great detail about how he was jobbed in 1913 because sportswriters didn’t have any idea what really drove offense.

“There is a certain charm about the phrase ‘.300 hitter’ which seems to appeal to the crowd,” he wrote. “If a man is a .300 hitter he is a star. I am not a statistician myself. I claim no ability to advise a system of batting averages which would be perfect or anywhere near it. But I do think that batting averages should do more than record the mere frequency of hits. They should do something to record the quality of hits.”

He was demanding slugging percentage all the way back in the Deadball Era!

And he was right! Cravath led the league in slugging in 1913.

“Someone will say I am complaining because I didn’t get the automobile,” Cravath wrote. “True, I think I earned it. But that isn’t the main thing.”

The main thing was that Hugh Chalmers was getting people to think about baseball in a new way.

“What Lipton is to yachting, what Vanderbilt is to auto racing, Hugh Chalmers is to baseball!” Ren Mulford told the crowd at the last awarding of cars in 1914.

What Mulford did not say—what he probably did not even know—was that Chalmers’ business was in decline. A War to End All Wars was beginning, and the economy was sagging. Chalmers’ “two kinds of car buyers,” had turned into one kind of car buyer, the kind that wanted a car for as little money as possible, and Henry Ford’s Model T dominated that market. Chalmers would spend the next years futilely trying to keep his company solvent.

And so, in 1915, he ended the Chalmers Trophy.

“The proposition of having a baseball hall of fame, as proposed by me, was to run for five years,” Chalmers explained. “With the presentation this year of the Chalmers Trophy to Eddie Collins and Johnny Evers, the work of the commission has come to an end. It seems unlikely now, and undesirable also, that we should continue these awards.”

It’s funny how he called his awards a “baseball hall of fame.”

The Chalmers Company went bankrupt in 1922. Hugh Chalmers died 10 years later—on a motor trip, no less—and Thomas F. McManus, a genius of automobile advertising, said, “Hugh Chambers did more than any other man to market the motor car.”

One year after the final Chalmers Trophy, Ring Lardner—baseball’s Mark Twain—added one final piece to the legacy. He wrote:

What makes this historic is… Lardner is, almost certainly, the first person who ever referred to the most valuable player as “MVP.” The Oxford English Dictionary only dates the “MVP” abbreviation to the 1940s. Lardner wrote his obituary for the Chalmers award in 1915.

From 1916 through 1921, there was no official most valuable player award. Sportswriters would muse every now and then about who might win it if the award actually existed, but nobody thought it would ever come back.

Then it reemerged in the most unlikely way.

Ban Johnson, the man who had banned individual awards, brought it back.

Johnson was still the president of the American League after surviving a bloody battle with commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. He grew to like the Chalmers Trophy. So, in 1922, he announced that the American League would start giving out an award of $1,000, along with a commemorative button, to the player who exemplified the highest achievement in performance and conduct on the field.

This time, the word “valuable” was not used, but Johnson basically had the same idea. He even used the same process; sportswriters would vote for the winning player using the same voting math that produced the Chalmers recipient. The new award did not have a name—it’s usually called the League Award now—but it did have clear criteria.

“All-around ability, faithfulness and freedom from accident, sickness, etc., will be considered in making the award,” Johnson announced.

“Faithfulness and freedom from accident, sickness, etc.” might seem like a strange thing to include—especially the “etc.” part—but there was probably a specific reason for it. The league’s greatest player, Babe Ruth, was (as usual) in the midst of a feud. Ruth had arranged to go barnstorming after the 1921 World Series. Landis forbade it, and warned Ruth that there would be a heavy penalty to pay if he ignored the commissioner’s bidding.

Obviously, Ruth went barnstorming anyway. Landis suspended him for the first six weeks of the season. Johnson despised Landis with the heat of a thousand suns, but he knew that he couldn’t get away with embarrassing the commissioner and giving Ruth the first League Award. So, with a few simple words—freedom from accident, sickness, etc.—he eliminated Ruth from consideration. The “etc.” does all the work.

As it turns out, Ruth probably wouldn’t have won the first League Award even if he had played all season. George Sisler hit .420 with 246 hits in 1922. He won in a runaway. Ruth did not get a single vote.

Ruth did win the League Award in 1923, and he won it unanimously.

That year, 1923, Ban Johnson grew obsessed with the idea of building an “American League Monument” in Washington, D.C., to commemorate the league he had created. This bizarre idea went so much further than you might expect. It won Senate approval and was debated in the House. A site in Potomac Park was selected. An architect created a blueprint. Johnson confidently announced that the names of every League Award winner would be etched into the monument, keeping the memories of those players alive forever.

When Babe Ruth won the League Award, he talked excitedly about having his name enshrined on a monument in Washington. “Hell,” he said, “if there aren’t any rules against it, I wonder if I can get my name up there twice.”

Ban Johnson ended that nonsense right away, by proclaiming that players were only eligible to win the League Award once.

The American League Monument quietly died in committee.

In 1924, the National League announced that they, too, would give out a $1,000 prize, plus a diploma to their most valuable player. The first National League winner was pitcher Dazzy Vance. Rogers Hornsby won it in 1925.

Meanwhile, because of the Babe Ruth Rule—one award per customer, no exceptions—the winners started to get a little bit weird. In 1925, Washington’s light-hitting shortstop, Roger Peckinpaugh, won in the American League. In 1926, George Burns won the AL award, and Bob O’Farrell won in the NL. In 1928, the American League gave the award to Mickey Cochrane, a great player, but one who didn’t have all that great a year. And so on.

And then, just like that, the leagues dropped the MVP award.

There’s a very good chance you’ve never heard of an old baseball man named Ernest Barnard. He was a sportswriter for a while, and then he joined the Cleveland Indians as the traveling secretary. He moved his way up to vice president (basically the team’s general manager) and in 1920, Cleveland won its first World Series. He obviously deserves his share of credit for that, though it does seem like the two key acquisitions—pitcher Stan Coveleski and centerfielder Tris Speaker—were the work of his predecessor, Bob McRoy.

Barnard was a respected guy all around baseball, and in 1927, a few months after Kenesaw Mountain Landis finally was able to take out his longtime nemesis, Ban Johnson, Barnard was named American League president.

To be honest, his four-year tenure as president—he died in 1931—is mostly forgettable. But he did achieve one long-lasting thing: In May of 1929, he announced that the American League would be dropping its most valuable player award.

He gave two reasons.

The voting was sometimes “unfair.”

He said the award caused strained relations between the players.

Both of these reasons were feints. Yes, of course, the voting could be uneven. And yes, there might have been some “jealousies and internal dissension,” as one unnamed baseball executive (probably Barnard) told a reporter. But neither of those reasons were at the heart of the decision.

No, at the heart of the decision was something both obvious and kind of hilarious: Players were using the award as evidence that they deserved more money. And the owners obviously couldn’t have that.

The most recent and blatant example was Mickey Cochrane. The Athletics’ catcher—and the player Mickey Mantle was named after—hit .293 with 10 home runs in 1928 and was named the most valuable player over probably, I don’t know, 20 more qualified candidates. Well, that’s what you get when you put a one-award limit on players—the voters couldn’t vote for Ruth or Gehrig, who were far and away the two best players in the league that year. Then, for whatever reason, the voters also chose Cochrane over eligible players who had better years, such as Goose Goslin and Heinie Manush and Lefty Grove and any number of others.

Anyway, Cochrane won the award. And in January, the Athletics sent him his contract. As United Press’ George Kirksey wrote: “The peeved Philadelphia Athletics catcher, who was awarded the American League’s most valuable player prize last season, was so surprised when he read the salary offered him, he exclaimed: ‘Why, there’s been a mistake! This can’t be my contract!’”

The holdout was not too long—Cochrane signed at the end of February—but it was bitter, and it was a headache that the owners didn’t want. As it turns out, it was also a headache that many sportswriters, even some of those who had actually voted for the award, didn’t want, either.

“The ball player so honored used the trophy as a lever to prize the managers loose for more cash,” Atlanta sports writer Morgan Blake wrote in his gloriously named column, “Sportanic Eruptions.” “He became a holdout the moment he obtained the prize.”

“Every player who has been named the most valuable player has gone right back to his boss the next year and demanded a raise in salary,” The Associated Press’ George Chadwick wrote. “And his principal argument has been to the owner, ‘I am the most valuable player in my league and in your club, and I want haversacks of dough. No use in you arguing that I am not the most valuable player, because I have the votes to show for it.”

It’s telling to see how enthusiastically sportswriters back then supported the owners in every single contract negotiation.

The National League most valuable player award lasted one more year—in 1929, they gave the award to Rogers Hornsby for a second time (wisely ending the whole one-player, one MVP rule) and then they, too, ended it. The National League also released a statement saying that the award was a widespread plague on the game. “It caused friction between players and manager, between managers and owners, and between players and owners,” Chadwick wrote. “There seemed to be no limit to the petty annoyances that it occasioned.”

But, you know: It came down to money. It always does, right?

And so the most valuable player award was dead. As one baseball executive told a reporter: “It shall never be revived.”

One of the wonderful parts of following a story like the history of the MVP award is all the wonderful people you meet along the way. Meet Alan J. Gould. What a guy. He grew up in Elmira, N.Y.—the place where the bank examiner in “It’s a Wonderful Life” lived—and at 16 he began writing part-time for his hometown Elmira Star-Gazette. After bouncing around for a few years, he was hired by the Associated Press to be a sportswriter.

Years ago, I wrote about Gould, and I called him the Forrest Gump of journalists because he seemed to show up everywhere. He was ringside for the Jack Dempsey-Gene Tunney fight. He was in Augusta when Gene Sarazen hit his famous double eagle in the second-ever Masters. He was in Berlin when Jesse Owens won gold medals under the outstretched arms of Nazi Germany. Heck, in 1948, when he was editor of the Associated Press, he was the one guy who kept his head on election night and announced to a shocked nation that, by gosh, Harry Truman was actually winning.

But whatever fame Alan J. Gould gained was because of one innovation: In 1935, while sports editor of the Associated Press, he began including his own Top 10 list of the best college football teams in the country. People were outraged. Well, very specifically, people in Minnesota were outraged. In his year-end ranking, Gould named Minnesota, Princeton and Southern Methodist as tri-national champions. For Golden Gophers fans, who had seen their team outscore opponents 194-36 in their 8-0 season, sharing the national title was infuriating, and they hung Gould’s likeness in effigy. “It created a storm,” Gould said modestly.

This made Gould… absolutely delighted. What, after all, were sports about if not to, in his own words, “keep the pot boiling.” He doubled down after the 1935 season, somehow found 44 sportswriters from around the country, and created the first-ever Associated Press college football poll.

“This,” he said proudly, “was just another exercise in hoopla.”

What does this have to do with the MVP? Well, seven years earlier, in 1929, Gould saw the void left behind by the American League’s abandonment of the MVP award. And so he put together a panel of sportswriters and gave out the Associated Press MVP award. The eight voters—one of whom was future commissioner of baseball Ford Frick—chose Cleveland’s Lew Fonseca, who had led the league with a .369 batting average.

And you know what happened? The newspapers covered it like crazy. It didn’t matter to them that this award was “unofficial.” It didn’t matter to them that this award came with no cash prize, no trophy, I don’t even think there was a certificate.

It should be said, the Associated Press was not the only organization to give out an MVP award that year. The Sporting News did, too… they gave the award to Al Simmons instead of Fonseca. But, honestly, even though The Sporting News was already being called “the Bible of Baseball,” few really bought into their award. No, Fonseca was the MVP because Alan J. Gould and the Associated Press said so.

In 1930, Gould tried it again, this time for both leagues. In the AL, the sportswriters chose Washington’s Joe Cronin. And in the NL, they selected the Cubs’ Hack Wilson, who that year had set the never-to-be-broken record of 191 RBIs. The Hack Wilson choice was given extra authenticity when Cubs president William J. Veeck—father of the more famous Bill Veeck—said the team would give Wilson the $1,000 prize that the league had stopped offering.

With that, the sportswriters realized something they might have known all along: They didn’t need the leagues’ approval or status or even their permission to give out the MVP award. They didn’t even need Alan J. Gould’s Associated Press. Nope, they could just give it out themselves… and people would care.

The president of the New York Chapter of the BBWAA was a guy named William J. Slocum—back in 1924, he created the New York BBWAA dinner (in honor of Kenesaw Mountain Landis), and this year that event celebrated its 100th anniversary.

Anyway, in December of 1930, Slocum announced that the BBWAA would start giving out the Most Valuable Player award themselves. Nobody paid too much attention when he first announced the plan. But, in October, when the group named Lefty Grove the American League MVP and Frankie Frisch the National League MVP, it was big news across America. The BBWAA even created silver trophies, 25.5 inches tall, to give to the winners at the New York dinner.

And the MVP trophy as we know it was born.

From 1931 to 1951, the MVP award—every single year—went to a player on a winning team. It didn’t always go to a player on the best team… but it usually did. From 1939 to 1952, at least one of the MVPs every year was from a pennant winner. Usually, both of them were from pennant winners.

The very idea of giving the MVP award to a player on a losing team was ludicrous.

Something happened in 1952, then, that was kind of hard to explain. The Brooklyn Dodgers won the pennant, and they had a fantastic MVP candidate, rookie Joe Black, who had gone 15-4 with a 2.15 ERA. He had pitched brilliantly in every role, and had been, in pretty much everyone’s estimation, the key to the Dodgers overcoming their rival Giants.

Then, in Philadelphia, the Phillies had played winning baseball, thanks largely to their ace, Robin Roberts, who had gone 28-7 while throwing 30 complete games.

Everybody assumed the MVP would come down to those two.

Instead, the award went to Cubs outfielder Hank Sauer.

The shock was palpable across the baseball world. Sauer had, indeed, led the league in home runs and RBIs. But he had slumped badly in the final month of the season. And, more to the point, the Cubs were not a winning team. They had gone 77-77-1 and had never been a factor in the pennant race.

It’s fair to say that a lot of people lost their minds in fury.

“The proper way to select the MVP would be to put all eight managers in a room and tell them they could have any athlete in the league,” Dick Kelly wrote. “How many do you suppose would take Hank Sauer over 25 or more others? The answer is none.”

“Perhaps the whole system should be changed to preclude some nonsense such as this,” Lawton Carver wrote. “A solution to all this may be to let the fans select by ballot the most valuable player.… Maybe a majority of fans do not know quite as much baseball as the writers. However, they couldn’t do any worse than the experts did this year.”

“What happened to the lame is debatable,” Oscar Fraley wrote, “but there can be no doubt today that the halt and the blind voted baseball’s most valuable player awards this year.”

The reaction against Sauer’s selection was so over-the-top that the nation’s leading sportswriter, Red Smith, felt like he had to say something.

The voting format has barely changed at all since Hugh Chalmers started this whole thing back in 1911. He chose sportswriters as voters; the sportswriters still vote. He had voters rank the players and then came up with a point system based on that ranking. The point system today is almost exactly the same.

And the instructions that go to voters haven’t changed much, either. Chalmers wanted voters to select the player who “should prove himself as the most important and useful player to his club and the league at large in point of deportment and value of services rendered.”

Then, Ban Johnson took over, and he wanted the MVP to go to the player who demonstrated the highest achievement in performance and conduct on the field based on “all-around ability, faithfulness and freedom from accident, sickness, etc.”

When the BBWAA started giving out the MVP in 1931, they gave three guidelines—votes should be based on:

Actual value of player to his team, that is, strength of offense and defense.

Number of games played.

General character, disposition, loyalty and effort.

Voters in 2024 were given these EXACT same guidelines. In other words, the language has been pretty much the same for more than 100 years.

But the voting hasn’t been the same. And yet, there have been many shifts in “what does valuable mean?” The 1952 vote for Hank Sauer was one of those that altered the trajectory of the MVP vote. After 1952, voters felt free to vote for players who were not necessarily on championship teams. The idea that a great player alone couldn’t make a team win was beginning to take hold, at least in the voting.

There are five other MVP votes that, I think, altered the trajectory of the vote.

Joe Medwick over Gabby Hartnett, 1937

Until 1937, the MVP math was simple. Each voter ranked 10 players. Then the voting was tallied using the same point system Hugh Chalmers had devised in 1911.

1st-place vote: 10 points

2nd-place vote: 9 points

3rd-place vote: 8 points

4th-place vote: 7 points

5th-place vote: 6 points

6th-place vote: 5 points

7th-place vote: 4 points

8th-place vote: 3 points

9th-place vote: 2 points

10th-place vote: 1 point

There was a sweet numerical purity to that particular system, and everybody seemed to like it. That is, until 1937. The National League MVP race was wide open in ’37. Looking back, it doesn’t make a lot of sense WHY it was so wide open. St. Louis’ Joe Medwick won the Triple Crown (even though nobody called it that back then. ). Medwick hit .374 with a league-leading 56 doubles, 31 homers, 154 RBIs and 111 runs.

But, at the time, as you know, winning was everything, and the Cardinals were pretty much a non-factor in the pennant race. As such, there was strong MVP support for Giants stars Carl Hubbell, Dick Bartell and Mel Ott (the Giants had won the pennant), Cubs catcher Gabby Hartnett (the Cubs had finished a close second), and even Boston’s 20-game winners Jim Turner and Lou Fette (the Bees had not been contenders, but they did surprise by finishing over .500 two years after losing 115 games).

The voting was quirky. Hartnett got one more first-place vote than Medwick (3-to-2) and they got the same number of second-place votes. But because Medwick got four third-place votes to Hartnett’s one, he took the MVP award by a score of 70-68.

That was an unsatisfactory result for the writers. In a vote that close, they believed the MVP shouldn’t go to the guy who got the most third-place votes. It should go to the guy who got the most first-place votes. And so in 1938, they changed the calculus—they made it so that a first-place vote was worth 14 points… and all the rest of the numbers would stay the same.

With this system in place, Hartnett would have won the 1937 MVP vote by three points.

Everybody seemed pleased with the new counting system. It mostly didn’t change the result, but every now and again it did. In 1944, for instance, Bill Nicholson was named on two more ballots than Marty Marion and, under the old system, would have won comfortably. But Marion got three more first-place votes and so he took the MVP award by a single point. Again, though, that was 1944, there were a few other things happening in the world at the time, and nobody particularly cared about the MVP voting system.

Three years later, though, they sure did.

Joe DiMaggio over Ted Williams, 1947

Before we get to the most controversial MVP vote in baseball history, let’s look at the statistics…

Joe DiMaggio: .315/.391/.522, 31 2B, 10 3B, 25 HR, 95 RBIs, 97 R, 4.8 WAR

Ted Williams: .343/.499/.634, 40 2B, 9 3B, 43 HR, 159 RBIs, 150 R, 9.9 WAR

Now, you can say—and you’d be right—that WAR wasn’t even invented in 1947. But let’s not kid anybody: Everybody knew Ted Williams’ numbers that year dwarfed DiMaggio’s. He won the Triple Crown again… and by now sportswriters were calling it the Triple Crown. Nobody was under any illusion that DiMaggio’s quantifiable value was anything close to that of Williams.

There was, of course, the enduring argument that Joltin’ Joe was an exponentially better defender and baserunner than Teddy Ballgame, and most years he was. But in ’47, DiMaggio—after having a bone spur removed from his left heel—was a shell of his former self. As the writers well knew, there were times he could barely walk… much less chase down fly balls in Yankee Stadium’s massive centerfield.

But, oh, the writers—particularly the New York writers—loved DiMaggio. They didn’t just love him personally (though some were, indeed, friends with him). It was about something bigger than that. They loved DiMaggio for the way he represented Hemingway’s courage, you know, grace under pressure. He gave the sportswriters a chance to be Hemingways themselves. They knew full well that DiMaggio was in pure agony throughout the 1947 season, and yet he played on without complaint, and he played well, and he led the Yankees to their first pennant since before D-Day. That story was irresistible, numbers be damned.

And DiMaggio won the MVP by one point.

“There hasn’t been this much indignation since George III put a tax on the tea that resulted in the celebrated Boston Tea Party,” Boston sportswriter John Drohan wrote in The Sporting News.

The vote totals from 1947 are truly wild. The first-place votes were divided among SIX different players.

Joe DiMaggio: 8 first-place votes

Joe Page, Yankees multi-use reliever who pitched in 56 games and went 14-4 with a 2.48 ERA: 7 first-place votes

George McQuinn, the Yankees’ 37-year=old first baseman who hit .304 with light power: 3 first-place votes

Ted Williams: 3 first-place votes

Eddie Joost, Philadelphia’s light-hitting shortstop who hit .206 with a league-leading 110 strikeouts: 2 first-place votes

Yeah that Eddie Joost thing is not a misprint

Lou Boudreau, Cleveland’s player-manager who hit .307 and led the league with 45 doubles: 1 first-place vote

We’ll get back to Joost. But first let me give you a few more facts about the 1947 voting. Thirty-four players received at least one vote, and that list included Washington’s part-time third baseman Mark Christman, who hit .222/.287/.281; Detroit’s 33-year-old slugger Roy Cullenbine, who hit .224 and was released after the season; and Athletics rookie pitcher Bill McCahan, who pitched 165 moderately effective innings.

The only player to be named on all 24 ballots was Lou Boudreau… and, yes, that does mean that one voter left Ted Williams off his ballot. The search for the person who left off Williams has been going for more than 75 years now… in part because Ted Williams put out an accusation in his book, My Turn at Bat.

Here’s the thing: It wasn’t Mel Webb who left Ted Williams off his ballot. For one thing, Boston’s Harold Kaese—no fan of Ted Williams—said that the voter who left off Williams was from the Midwest and that the three first-place votes Williams got were “probably the Boston representatives.” For another, Webb wrote a glowing story about Williams’ remarkable season just a couple weeks after the vote. We still don’t know who left off Williams.

Anyway, the big problem wasn’t the guy who left Williams off his ballot. The big problem was that two voters gave their first-place votes to Eddie Joost, and three first-place votes went to George McQuinn. “In all sense of fairness and justice, how could they pass up Ted Williams?” Red Sox GM Joe Cronin asked about those writers. One sportswriter wondered if the writers who chose Joost were playing a practical joke.

The final jolt from 1947 is that if the vote had been counted under the original 10-9-8 point system, Williams would have won easily.

Anyway, the MVP came of age that year. There had been controversial votes before—a couple of them involved Williams—and there would controversial votes again, but this one captured the imagination of America.

Intermission: Is It Easier to Win an MVP Award in New York or Texas?

Before we get to the next pivotal vote, let’s pause for this question. DiMaggio winning the MVP over Williams (twice!) and the multiple MVP wins for Yogi Berra, Roger Maris, Mickey Mantle and so on strongly suggest that it’s much easier to win an MVP award as a Yankee than, say, a Ranger. Is that actually true, though?

Well, I do think that was true at one time. I don’t think it has been true for years, though.

Here are the team-by-team rankings of MVPs, going all the way back to the Chalmers Awards:

New York Yankees: 23

St. Louis Cardinals: 21

Los Angeles/Brooklyn Dodgers: 14

San Francisco/New York Giants: 14

Oakland/Philadelphia Athletics: 13

Boston Red Sox: 12

Cincinnati Reds: 12

Detroit Tigers: 12

Chicago Cubs: 11

Atlanta/Milwaukee/Boston Braves: 9

Minnesota Twins/Washington Senators: 8

Philadelphia Phillies: 8

Pittsburgh Pirates: 8

California/Anaheim/Los Angeles/Whatever Angels: 7

Baltimore Orioles/St. Louis Browns: 6

Texas Rangers: 6

Chicago White Sox: 5

Milwaukee Brewers: 5

Cleveland Indians/Guardians: 3

Houston Astros: 2

Seattle Mariners: 2

Toronto Blue Jays: 2

Colorado Rockies: 1

Kansas City Royals: 1

Miami Marlins: 1

San Diego Padres: 1

Washington Nationals/Montreal Expos: 1

Arizona Diamondbacks: 0

New York Mets: 0

Tampa Bay Rays: 0

So that probably looks the way you’d expect it to look. Before getting to the Yankees and Rangers, I would say that if any team has a gripe about the MVP voting, it’s Cleveland. The Guardians/Indians have had only four MVPs in their long history, and no Clevelander has won an MVP award since Al Rosen in 1953. Cleveland has had 10 players finish second or third in the MVP voting in those years:

Larry Doby in 1954: Finished 2nd (Yogi Berra)

Al Smith in 1955: Finished 3rd (Yogi Berra)

Rocky Colavito in 1958: Finished 3rd (Jackie Jensen)

Albert Belle in 1994: Finished 3rd (Frank Thomas)

Albert Belle in 1995: Finished 2nd Mo Vaughn)

Albert Belle in 1996: Finished 3rd (Juan Gonzalez)

Robbie Alomar/Manny Ramirez in 1999: Finished 3rd (Iván Rodríguez)

Michael Brantley in 2014: Finished 3rd (Mike Trout)

José Ramírez in 2018: Finished 3rd (Mookie Betts)

José Ramírez in 2020: Finished 2nd (José Abreu)

But getting back to the Yankees and Rangers—it’s true that overall the Yankees have the most MVPs. But the Rangers have only been in existence since 1972. And since 1972, the Rangers have six MVPs. The Yankees also have six MVPs since ’72.

Rangers:

1972: Jeff Burroughs

1996: Juan González

1998: Juan González

1999: Iván Rodriguez

2003: Alex Rodriguez

2010: Josh Hamilton

Yankees:

1976: Thurman Munson

1985: Don Mattingly

2005: Alex Rodriguez

2007: Alex Rodriguez

2022: Aaron Judge

2024: Aaron Judge

You look at that, and then you think about how much more success the Yankees have had than the Rangers since 1972 and you realize something kind of shocking: There was a time, yes, when a Yankee seemed to win the MVP every year, and many of those awards were suspect. But these days it’s probably a disadvantage to be a Yankees player when it comes to the biggest awards. Derek Jeter never won an MVP. Mariano Rivera never won an MVP or a Cy Young. The Yankees have won seven World Series since 1977. They did not have an MVP in any of those years. Wild.

Rollie Fingers over Rickey Henderson, 1981

From the start, the people running these MVP contests have reminded voters repeatedly: Do not forget the pitchers. Only one of the eight Chalmers winners was a pitcher—that was Walter Johnson in 1913. Then, only two of the 13 League Award MVPs were pitchers.

The BBWAA felt so strongly that pitchers were being undervalued that they included a sentence in their instructions to voters that trumpeted: “Pitchers are eligible for the award.”

It sort of worked—almost a quarter of the MVPs handed out between 1931 and 1956 (12 out of 52) went to pitchers. Then, in ’56, the BBWAA began giving out the Cy Young Award to pitchers, and even though everybody kept insisting that pitchers should still be given full consideration for MVP, well, only four pitchers won the award over the next quarter century.

Sandy Koufax, 1963

Bob Gibson, 1968

Denny McLain, 1968

Vida Blue, 1971

Even though starting pitchers dominated the nine seasons after Blue’s victory—11 of the 18 WAR leaders were pitchers—none won an MVP award. Truth is, none came all that close. In 1978, Ron Guidry came closest when he went 25-3 with a 1.74 ERA and finished second in the MVP balloting to Jim Rice. But the margin between them was more than 60 points. If that year didn’t win a starter the MVP award, well, there really wasn’t much hope.

Then came 1981. It was the strike year, so 50-plus fewer games were played, and the stats were wonky and unimpressive to look at. The American League MVP favorite had to be Oakland’s dynamic, 22-year-old leftfielder, Rickey Henderson, who hit .319, stole 56 bases, and scored 89 runs in just 108 games. He was thrilling, and he led Billy Martin’s A’s to the playoffs.

The voters went in a completely different direction.

They selected Milwaukee Brewers closer Rollie Fingers. He was the first relief pitcher to ever win the American League MVP award. And he won it by pitching 78 innings.

“I was certainly surprised,” Fingers said.

Fingers’ season was unquestionably delightful. He was 34 years old and nearing the end. During the offseason, he had been traded twice—the second time to Milwaukee. And then he was marvelous: He allowed just nine runs all season, the league hit .198 against him, he allowed just two runs and four walks in his last 23 appearances combined.

“I didn’t think I still had a year like this in me,” he said.

Even so, his election was just plain strange. But, as it turns out, it was a sign: The BBWAA writers had mostly given up on starting pitchers as MVP candidates. But, as save totals began to skyrocket—the save was still an exciting new statistic then—the writers were about the go relief pitcher crazy.

In 1984, they gave the award to Detroit reliever Willie Hernández, who had never been a closer before. Royals reliever Dan Quisenberry finished third.

The very next year, Dwight Gooden had perhaps the best starting pitcher season of the last half-century—he went 24-4 with a 1.53 ERA. He finished fourth in the MVP voting. Starters were mostly out (Roger Clemens did win the MVP in 1986). Relievers were mostly in! Dennis Eckersley won the 1992 MVP while pitching 80 innings. In that wild time, Kent Tekulve, Goose Gossage, Dan Quisenberry, Bruce Sutter, Mark Davis, Bobby Thigpen and Lee Smith all received considerable MVP consideration.

I mean, look at this fun!

1993 National League voting

Greg Maddux (20-10, 2.36 ERA, led league in innings): 17 MVP points.

Giants closer Rod Beck (79 innings, 48 saves): 23 MVP points

1994 American League voting

Randy Johnson (18-2, 2.48 ERA, 294 Ks): 111 MVP points

Cleveland closer Jose Mesa (64 innings, 46 saves): 130 MVP points

1997 American League voting

Roger Clemens (21-7, 2.05 ERA, 292 Ks, 12.1 bWAR): 56 MVP points

Baltimore closer Randy Myers (59 innings, 45 saves): 128 MVP points

It was like a fever dream.

In time, the fever broke. The voters stopped directly connecting saves with value. A couple starters—Justin Verlander and Clayton Kershaw—won MVP awards in the early 2010s. No reliever has won the MVP since Eck. No full-time starting pitcher has won the MVP since Kershaw in 2014.

But one part-time pitcher has won two MVPs. Shohei, of course. Turns out if you can pitch AND hit, the voters will still love you.

Andre Dawson over Tony Gwynn, 1987

You certainly know about Branch Rickey’s famous line to Ralph Kiner. This came after the 1952 season. Kiner was shocked to find that Rickey, then Pittsburgh’s general manager, had cut his salary. Kiner barged in to confront the Mahatma with a few basic facts, including that he had just led the National League in home runs.

Rickey, as usual, was nonplussed by the assault.

“We could have finished last without you,” he said.

Rickey has been much-celebrated for that line, and that’s always bugged me, because (A) It was a cheap shot to laugh off cheating a player out of his fair value, and (B) It’s utterly absurd and unfair. The Pirates didn’t finish in last place because of Ralph Kiner. The Pirates finished in last place in 1952 because of Branch Rickey and the dreadful team he had assembled around Ralph Kiner. And you know Rickey wasn’t returning any of his salary.

But, hey, the line is funny… and for many years it guided the MVP voting.

In the entire history of the MVP awards up to 1987—that includes the Chalmers Trophies and the League MVPs—only two players from losing teams were selected as the Most Valuable Player.

They were both Chicago Cubs.

The first—well, technically, the first two—was Ernie Banks. He won the 1958 and 1959 MVP awards for losing Cubs teams. He won both of them convincingly because he was that good and that beloved. Nobody had ever seen a shortstop hit the way Ernie Banks hit.

The second was Andre Dawson in 1987.

It was a huge deal when Dawson won the award. Well, it was a beautiful story. The Hawk was one of the best and most dynamic players in baseball, but he was generally underappreciated because he had spent his career in Canada. He was also somewhat worn down because he had spent his career on the brutal artificial turf at Montreal’s Stade Olympique. His knees, in particular, were an issue when he became a free agent at the end of the 1986 season—or anyway, that was the excuse colluding owners used for not making him offers.

He publicly campaigned for a chance to sign with the Cubs. And the Cubs—because, you know, collusion—refused to sign him and claimed that they would rather have 30-year-old pinch-hitter Brian Dayett in the outfield. Then Dawson and his agent, Dick Moss, made the Cubs an offer they couldn’t refuse: a blank contract. The Cubs were told they could fill in any amount they wanted for one year, and Dawson would play under those terms.

Even a colluding owner couldn’t turn down a deal like that, and the Cubs wrote in $500,000—less than half of what Dawson had been paid as a perennial All-Star—and Dawson signed the deal and then had a spectacular statistical season. He led the league in home runs (49), RBIs (137) and total bases (353). He became the first player to ever win the MVP award with his team finishing in last place.

At the time—and, yes, even now—there are those who will argue that the award should have gone to second-place finisher Ozzie Smith, who had his best offensive season (hit .300 for the only time and scored 100 runs) to go along with his typically legendary defense. It’s a fair argument now. It was also a fair argument then, when the MVPs almost always went to a player on a first-place team. The Cardinals beat out the Cubs by 19 games that year and ended up winning the pennant.

But, you know what? Looking back, the 1987 MVP should have gone to ANOTHER player from a DIFFERENT last-place team.

In 1987, Tony Gwynn had a truly historic season. To start with, he hit .370. No National Leaguer had hit .370 in a season in almost 40 years, going all the way back to Stan Musial in 1948.

On top of that, Gwynn stole 56 bases. The last National Leaguer to combine a .370 average with 56 stolen bases? Yeah, that would be John McGraw in 1899. And it was kind of a different game in 1899.

On top of THAT, Gwynn won the Gold Glove. You can’t necessarily count on Gold Glove voting to offer a clear-eyed view of a player’s defense, but the defensive stats show that Gwynn was a standout defensive rightfielder in 1987.

A .370 average? Fifty steals? A Gold Glove? Only one player has ever done all three of those things in the same year. That one player was Tony Gwynn in 1987.

Gwynn finished eighth in the MVP voting.

Looking back, Baseball-Reference WAR and FanGraphs WAR both have Gwynn as the best player in the league and MUCH more valuable than Dawson. But… the Padres lost 95 games that year, and Gwynn didn’t have the compelling narrative that Dawson had, and that was that. Gwynn never won an MVP award, and only once finished in the top five. A huge part of that is that he rarely played on a team that contended.

After the Dawson vote, sportswriters did uncouple the MVP award from team success somewhat. In 1989, Robin Yount won the award playing for an up-and-down, 81-81 Brewers team. In 1991, Cal Ripken Jr. won the MVP even though his Orioles lost 95 games. In 2003, Alex Rodriguez won the MVP for a hugely disappointing, 91-loss Rangers team.

And today? Well, three of the last five American League MVPs played on losing Angels teams—Mike Trout and Shohei Ohtani twice.

An MVP Parade!

Before we get to our fifth and final award-altering MVP vote—Miguel Cabrera over Mike Trout in 2012—well, 13 years ago (ironically or fittingly right before the Miggy-Trout season), I wrote an article called “The MVP Formula.” I totally forgot about this article, which leads off with a passionate section about how Babe Ruth was the greatest player of all time, news that certainly would have surprised the author of The Baseball 100 less than 10 years later. Ah, we do change with the years, don’t we?

But, here’s the main thing: In that article, I wrote about every one of the 44 MVP races where the winner had an OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) at least 10% below the OPS leader. Since I did the research back then, and we’ve already come this far, I’ll show you all 44 of those races again with a quick “Why did he win?” sentence.

1931: Frankie Frisch over Chuck Klein

Difference in OPS: 22.2%

Why: Frisch was celebrated for his intangibles, and his Cardinals won the pennant. Also, Klein’s OPS was greatly aided by his ludicrous home ballpark, the Baker Bowl.

1934: Mickey Cochrane over Lou Gehrig

Difference in OPS: 28.3%

Why: This is one of the most egregious choices in the award’s history—both of Cochrane’s MVP choices are shaky at best—but Cochrane was a catcher, a leader (literally; he was the team’s manager) and his Tigers won the pennant.

1935: Gabby Hartnett over Arky Vaughan

Difference in OPS: 13.6%

Why: To the winners go the spoils; Hartnett’s Cubs won the pennant. Also, Hartnett was a catcher and, as you will see, MVP voters love catchers.

1937: Charlie Gehringer over Lou Gehrig

Difference in OPS: 12.4%

Why: Hard to explain this one, since the Yankees won the pennant by 13 games. Gehringer did lead the league in hitting. Also, Gehrig was not even the top MVP choice for the Yankees; Joe DiMaggio hit .346 with 46 homers, 167 RBIs and 151 runs. Gehrig and DiMag must have split the Yankee vote (though, somehow, Gehringer didn’t split the Tiger vote with Hank Greenberg, who drove in 184 runs that year).

1938: Ernie Lombardi over Johnny Mize

Difference in OPS: 11.7%

Comments: Lombardi was a catcher, and he won the batting title over Mize in grand style by refusing to sit on the last day. Winning didn’t play a big role in ’38 since neither player’s team won a championships. The Cubs won the pennant, and their top MVP candidate was pitcher Bill Lee (not that Bill Lee).

1940: Frank McCormick over Johnny Mize

Difference in OPS: 18.3%

Comments: Poor Johnny Mize. For the second straight year, he had the MVP taken away, this time by a slick-fielding first baseman whose Reds won the pennant.

1941: Joe DiMaggio over Ted Williams

Difference in OPS: 15.9%

Why: DiMaggio over Ted Williams in 1941 was egregious—this was the year Ted hit .400—but not nearly as egregious as 1947. This was, after all, the year of DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak, and he was still at the height of his powers as an all-around player.

1942: Joe Gordon over Ted Williams

Difference in OPS: 21.5%

Why: The why is easy—the Yankees won the pennant by nine games over the Red Sox—but, as I wrote 13 years ago, something else should be said here: Gordon’s MVP in 1942 has been much-maligned, and you get it: Williams was definitely better. Heck, he won the Triple Crown. BUT, Joe Gordon had a really good season, too. I mean, it was an 8-WAR season. This isn’t a case of an undeserving player winning MVP (which has happened many times). This is a case of a deserving player winning over a perhaps more-deserving player.

1944: Marty Marion over Stan Musial

Difference in OPS: 30.7%

Why: I wrote above about how the new point system gave Marion the MVP over Chicago’s Bill Nicholson. Musial didn’t really figure in the balloting; he finished fourth. I think that’s because he won the MVP in 1943.

1947: Joe DiMaggio over Ted Williams

Difference in OPS: 19.4%

Why: See above.

1947: Bob Elliott over Ralph Kiner

Difference in OPS: 12.1%

Why: They called Bob Elliott, “Mr. Team.” They did not call Ralph Kiner that.

1948: Lou Boudreau over Ted Williams

Difference in OPS: 11.2%

Why: Boudreau was Cleveland’s player-manager and the Indians won the pennant. He was also the better defensive player. He also came up with the Boudreau shift, specifically to stifle Ted Williams.

1949: Jackie Robinson over Ralph Kiner

Difference in OPS: 11.8%

Why: Jackie Robinson was a much better all-around player, and the Dodgers won the pennant, and the Pirates were terrible. Kiner led the league in OPS three times. He got one first-place MVP vote in his entire career.

1950: Phil Rizzuto over Larry Doby

Difference in OPS: 13.1%

Why: The why, again, is easy—the Yankees won the pennant, Rizzuto had his best offensive season and was a defensive whiz and team leader. The sad part is that Doby finished EIGHTH in the MVP balloting. In my original version of this MVP rundown, I wrote about how there were nine African-American MVPs in the National League between 1949 and 1959—all of them played in the Negro leagues. The first Black MVP in the American League was Elston Howard in 1963. I don’t think this was a reflection of the voters as much as it was a reflection of how slowly American League teams moved to add Black players.

1951: Yogi Berra over Ted Williams

Difference in OPS: 17.4%

1954: Yogi Berra over Ted Williams

Difference in OPS: 25.5%

1955: Yogi Berra over Mickey Mantle

Difference in OPS: 21.4%

Why: The voters loved themselves some Yogi Berra. Then again, don’t we all love Yogi Berra?

1958: Jackie Jensen over Mickey Mantle

Difference in OPS: 10%

Why: I think this comes down to Mantle having won the MVP award in 1956 and 1957—it was just somebody else’s turn. Now, why was it Jensen rather than, say, Rocky Colavito or Bob Cerv or even the aging Ted Williams, who was incredible in his 121 games? My guess: It came down to Jensen having led the league in RBIs.

1959: Nellie Fox over Al Kaline

Difference in OPS: 18.2%

Why: It was the White Sox’ year—they won the pennant—and so somebody on Chicago was winning the MVP. Fox was unquestionably the team’s leader, and he played in 156 games, an achievement in a 154-game season.

1960: Dick Groat over Frank Robinson

Difference in OPS: 23.7%

Why: It was the Pirates’ year—the won the pennant—and so somebody on Pittsburgh was winning the MVP. Groat led the league in hitting, so he was that somebody. Roberto Clemente, who led the Pirates in RBIs, felt slighted.

1961: Roger Maris over Norm Cash

Difference in OPS: 13.6%

Why: The answer is easy and can be summed up in one number and one punctuation mark: 61*.

1962: Maury Wills over Frank Robinson

Difference in OPS: 31.1%

Why: The answer is easy and can be summed up in one number: 104. That’s the number of stolen bases Wills had in 1962… nobody in the National League had stolen even 50 bases since the early 1920s.

1964: Ken Boyer over Willie Mays

Difference in OPS: 13.7%

Why: The Cardinals came back from oblivion to take the pennant, and Boyer was a big reason why—he led the league with 114 RBIs. But Mays was beyond incredible in 1964; it’s one of the greatest seasons in baseball history not rewarded with an MVP.

1964: Brooks Robinson over Mickey Mantle

Difference in OPS: 12.4%

Why: The Yankees did win the pennant, but the Orioles (and White Sox) made a gallant run and Brooksie had his best offensive season to go along with his unmatched defense.

1965: Zoilo Versalles Over Carl Yastrzemski

Difference in OPS: 16.2%

Why: It was the Twins’ year—they won the pennant—and so somebody on Minnesota was winning the MVP. The other option was Tony Oliva, who led the league in batting, but the voters went almost unanimously for Versalles’ all-around play.

1966: Roberto Clemente over Dick Allen

Difference in OPS: 12.8%

Why: The Dodgers won the pennant and their obvious MVP candidate was Sandy Koufax, who actually got more first-place MVP votes than Clemente. But Koufax had already won an MVP, and Clemente had been this remarkable and much-admired player for a decade, and it was just his time.

1970: Johnny Bench over Willie McCovey

Difference in OPS: 11.7%

Why: Even though McCovey had a higher OPS (mostly because he led the league with 137 walks), nobody in 1970 would have said he had a better offensive year than Bench, who led the league in home runs and RBIs. He was also the best defensive catcher anybody had ever seen. This was a runaway.

1973: Pete Rose over Willie Stargell

Difference in OPS: 19.3%

Why: The Reds won the West, the Pirates finished below .500, Rose led the league in hitting… that’s what gave Pete the edge over Pops in a very close vote.

1974: Steve Garvey over Willie Stargell

Difference in OPS: 14.1%

Why: Two years in a row that Stargell led the league in OPS and didn’t take the MVP. This year, he didn’t even come close—the Dodgers won the pennant and Garvey, Captain America, was viewed as the impeccable leader of the Boys in Blue.

1976: Thurman Munson over Hal McRae

Difference in OPS: 11.4%

Why: Munson was a catcher and the rough-and-tumble leader of the Bronx Zoo Yankees when they reemerged after a few years in the wilderness. George Brett, who led the league in hitting, finished a distant second to Munson; McRae, as a designated hitter, didn’t even get a first-place vote.

1979: Don Baylor over Fred Lynn

Difference in OPS: 14.9%

Why: Baylor’s Angels won the American League West, while Lynn’s Red Sox finished a distant third. So that was what likely made the difference, along with Baylor’s league-leading 139 RBIs. But what’s funny is: Lynn’s Red Sox actually won more games than Baylor’s Angels.

1985: Willie McGee over Pedro Guerrero

Difference in OPS: 11.2%

Why: McGee won the batting title and Guerrero missed 25 games with injuries. Heck, Guerrero didn’t even finish second—that went to Dave Parker, who led the league with 125 RBIs. The real travesty of 1985 is that Dwight Gooden finished fourth.

1987: Andre Dawson over Jack Clark

Difference in OPS: 15.1%

Why: See above.

1995: Mo Vaughn over Edgar Martinez

Difference in OPS: 13%

Why: One fun thing for people of my generation is to try and explain why Fred McGriff was nicknamed the Crime Dog—it’s a LONG story. Same with the 1995 American League voting. You have to explain that the writers hated Albert Belle, who had 50 doubles and 50 home runs and tied Vaughn for the RBI title. You have to explain that Edgar was a designated hitter and spent his whole career being underrated. You have to explain that Randy Johnson was incredible but MVP voters had lost interest in starting pitchers. It’s a whole thing.

1995: Barry Larkin over Barry Bonds

Difference in OPS: 12.2%

Why: The Reds won the division, Larkin was the king of intangibles, and Bonds’ Giants finished with a losing record. He finished 12th in the voting.

1996: Juan Gonzalez over Mark McGwire

Difference in OPS: 15.6%

Why: Again, Albert Belle plays a role. He, not Juan Gone, led the league in RBIs. But Gonzalez was second, and the voters weren’t going to pick Belle, so the award went to Gonzalez. The crazy part is that the voters didn’t give the award to Ken Griffey Jr., who was SO much better and so much more popular. That comes down to the Rangers winning the division.

1998: Sammy Sosa over Mark McGwire

Difference in OPS: 16.2%

Why: This vote doesn’t get nearly enough criticism. Sosa dominated the voting (30 first-place votes to 2!). But McGwire was WAY better than Sosa in the Year of the Homer. I mean, it’s not even close—there are 200 points of OPS between them. BUT Sosa won the RBI battle and the Cubs snuck into the postseason as a wild card.

1999: Ivan Rodriguez over Manny Ramirez

Difference in OPS: 17.3%

Comments: Pudge beating out Pedro Martinez in 1999 is one of the wackier votes ever—Pedro got more first-place votes but was left off two ballots because he was a pitcher. But it shouldn’t be overlooked that MannyBManny drove in 165 runs in ’99, in addition to leading the league in OPS.

2000: Jeff Kent over Todd Helton

Difference in OPS: 12.2%

Why: The Giants won, Kent led the Giants in RBIs, voters had grown increasingly unimpressed by Coors Field numbers and increasingly sick of Barry Bonds. This is the result.

2001: Ichiro Suzuki over Jason Giambi

Difference in OPS: 26.3%

Why: Ichiro created a mania, he led the league in hitting, and the Mariners won 116 games.

2002: Miguel Tejada over Jim Thome

Difference in OPS: 23.2%

Why: The A’s won 103 games and Tejada played all 162 games at shortstop. Big Jim was a designated hitter serving as a first baseman for a losing team.

2006: Justin Morneau vs. Travis Hafner

Difference in OPS: 14.9%

Why: This will always be remembered as Morneau over Derek Jeter—again, it came down to RBIs—but Hafner led the league in slugging and OPS, and that should be remembered.

2007: Jimmy Rollins over Chipper Jones

Difference in OPS: 15%

Why: The Phillies won the pennant, the Braves didn’t, and J-Roll’s numerical buffet—20 doubles (38, actually), 20 triples (exactly), 20 homers (30), 20 stolen bases (41), plus a Gold Glove at shortstop—wowed the voters.

2008: Dustin Pedroia over Milton Bradley

Difference in OPS: 13%

Why: The Red Sox won, Pedroia was the leader; this one’s easy. But it’s a reminder that Milton Bradley really did lead the league in OPS one year, though he played in only 126 games.

Miguel Cabrera over Mike Trout, 2012

Now, finally, it’s time for the last frontier—or at least the latest frontier—of MVP voting… and our big finish.

Before Miggy and Trout, going all the way back to Hugh Chalmers, the debate about the MVP, and more specifically the debate about baseball value, has come down in many ways to that clash between offensive statistics and so-called intangibles. You’ll remember the very first Chalmers Trophy of 1910 was meant for the batting champion. That was the original thought: The numbers would do the choosing. The assumption in those days was that the batting champion—batting average being the most vital and important statistic of the day—HAD to be the most valuable player.

When the race for the first Chalmers Trophy blew up, the paradigm shifted. Voters were given the choice. Of course, they could have voted for the batting champion—and sometimes they did. They could have voted for the pitcher with the most wins—and sometimes they did. They could have voted for the player with the most RBIs, the most stolen bases, the most saves, the most home runs. And sometimes they did.

But sometimes, they went in other directions. Sometimes, they chose an MVP because of how they hit in the clutch. Sometimes they chose an MVP based on leadership. Sometimes, fielding came into play. Sometimes, they defaulted to the best player on the best team. Sometimes they fell in love with a story. The MVP choices were sometimes inspired and sometimes ridiculous, but that basic tension between the stats and something uncountable was always there at the forefront of the conversation. And it was interesting.

In 2012, though, the argument changed. This time, it wasn’t about statistics and intangibles.

It was about old statistics and new statistics.

Representing the old statistics was Miguel Cabrera. He won the Triple Crown in 2012 for a Tigers team that ended up winning the pennant. In other years, he would have won the MVP unanimously.

Representing the new statistics was a 20-year-old rookie, Mike Trout, who hit a few points lower than Cabrera, hit 14 fewer homers, knocked in 56 fewer runs, and played in 22 fewer games. He did all this for an Angels team that did not make the postseason.

It’s hard to say just where Trout would have finished in the MVP balloting 10 or 20 or 50 years earlier. It’s not like a 20-year-old rookie hitting .326 with 30 home runs and 49 steals would have ever gone entirely unnoticed. But I’m certain he would have received no first-place votes, and he probably would have finished no higher than fifth or sixth.

But in 2012, Wins Above Replacement had become the it statistic. WAR combines so many of those things previously called intangibles—fielding, baserunning, the ability to stay out of the double play, ballpark effects and so on—into one tidy number that is basically meant to approximate how many more wins the player will contribute to the team over some random and imaginary player who might replace him. Unlike batting average or ERA, it’s a difficult statistic to calculate. But it’s a very easy statistic to comprehend. You want the player who can get your team more wins.

And by WAR, Trout was the superior player—WAR calculated that he was worth three or so more wins than Cabrera because he was the better defender, because he was the better baserunner, because he played a more valuable defensive position, because he put up his outstanding numbers in a tougher hitting park, and so on.

WAR did not win the Battle of Trout and Cabrera. Trout did get six first-place votes, but Miggy got 22 and ran away with the award. A year later, Trout again led the league in WAR, but Miggy took the MVP award again.

Ah, but in the end, WAR seems to have won the war.

Let me show you the chart that might blow your mind (or might just confirm what you already know). I looked at an era-by-era average difference in Baseball-Reference WAR between the MVP and the WAR leader (I used bWAR for simplicity). Obviously, when the MVP and WAR leader are the same player, the difference is 0. When the voters pick Ryan Howard over Albert Pujols or Justin Morneau over Johan Santana, though, the difference is 3.3 as it was in both those cases.

First, here’s a fun fact: The largest difference between the WAR leader and the MVP is probably not the one you think. That is to say, it’s not Ted Williams over Joe DiMaggio in 1947 (4.8 difference) and it’s not Willie Mays over Ken Boyer in 1964 (4.9 difference) and it’s not Dwight Gooden over Willie McGee in 1985 (5.1 difference).