Free Friday: Jeterating (Again)

OK, I’m hitting the road!

Saturday: I’m in Fort Myers at the Southwest Florida Reading Festival! Come on out!

Tuesday, March 5: I’m in Boca Raton!

Thursday, March 7: Kansas City, here I come.

Saturday and Sunday, March 9-10: I’m all over the place at the Tucson Festival of Books.

Sunday, March 17: Cleveland Rocks!

Saturday and Sunday, March 23-24: Cincinnati for a book talk and to accept the CASEY Award for WHY WE LOVE BASEBALL.

Hope to see you out there. And while I’m on the road, I will be handing out super-awesome postcards about my upcoming book, WHY WE LOVE FOOTBALL. I’m going to run out today to get a silver Sharpie in order to sign those cards. They’re pretty sweet, I have to say.

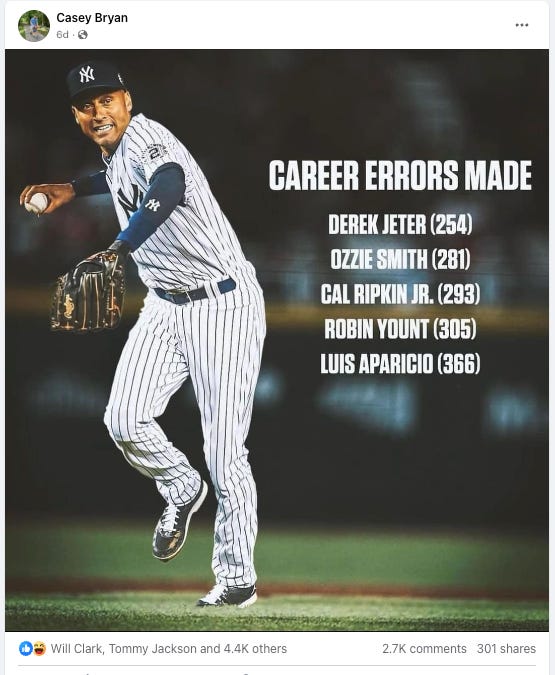

Every time I think I’m out, they pull me back in. Brandon McCarthy made sure to send me this, which I believe has been making the rounds:

And, as Brandon undoubtedly knew, I have spent way too much time thinking about this—way more time than I should spend thinking about a graphic from a Jeter fan that misspells Cal Ripken’s name. But I believe there is a sense, one I believe will grow the longer the years go on, that Derek Jeter was a good defensive shortstop. And he most certainly was not. I don’t know if he was the worst every-day defensive shortstop in baseball history, as the numbers suggest, but he was much closer to that than a good defensive shortstop, and so I cannot help but try to think of a simple chart to counter this nonsense.

And, as it so happens, I have thought up one.

You all probably know what “range factor” is. It’s a Bill James creation, and I like it because it offers no judgment. To calculate range factor, you simply add up putouts and assists and divide it by games played. That simple. If a shortstop makes 35 putouts and assists in a seven-game week, he has a range factor of 5 for that span. Nobody’s asking how many plays he SHOULD have made or how many plays he MIGHT have made. It’s just simple math.

Math note: I use range-factor per nine innings, which is only the tiniest bit more complicated. Take the same shortstop over seven games—but let’s say he played in 61 innings because his team lost twice on the road. So his range factor per nine innings would be 5.16 ((35 x 9) / 61). I think that’s just a little bit more precise.

So here’s something cool: You can use the player’s range factor to calculate the number of plays made. Then you can use the league-average range factor to calculate the number of plays an average shortstop would have made in the same number of innings. Fun, right? Let’s just pick Andrelton Simmons as an example.

Simmons played 10,338 innings and had a range factor of 4.46. That means he made 5,123 plays over his career.

The league-average range faector over his career is 4.12. That means the average shortstop would make 4,733 plays over the same time period.

Take Simmons’ plays, subtract the average shortstop plays, voila, you see that Simmons made 390 more plays than the average shortstop might have made.

Obviously, it’s just a projection and somewhat imperfect… but what statistic isn’t? We’ll call these PAA—Plays Above Average—and Simmons, as you would expect, has one of the highest totals per nine-inning totals in baseball history. Specifically, he has the sixth-highest, but we’ll get to that. You might be surprised to see who is at number one when you break it down that way.

Happy Friday! Our Friday posts are free so everyone can enjoy them. Just a reminder that Joe Blogs is a reader-supported newsletter, and I’d love and appreciate your support.

But before we get there, let’s look at raw numbers. Here are the five shortstops with the most PAA in baseball history:

Ozzie Smith, 1,065

Dave Bancroft, 768

Rabbit Maranville, 611

Troy Tulowitzki, 559

Dick Bartell, 540

Yeah, no surprise at the top. It’s a little bit comical to me whenever I hear anybody—ANYBODY—compared directly to Ozzie Smith as a defensive shortstop. I tend to be one of those people who believes players are getting better, and I try not to get stuck thinking that some player I idolized can never been surpassed. But Ozzie was a unicorn in the truest sense of the word. He was not only the most dazzling defender who ever lived, he was also the most productive. He was Barry Sanders and Emmitt Smith COMBINED.

His 621 assists in 1980 is not only the all-time record for a single season, it will always be the record, forever and ever, because these days, with all the strikeouts and with shortstops rarely playing 162 games, almost nobody gets 400 assists, much less 500, much less 621. Last year, Francisco Lindor led all of baseball with 396 assists.

Of course, Ozzie played in a different time. But he so towered over his time—he led the league in assists eight times—and he did it in such spectacular and glorious fashion, no, there is Ozzie and there is everybody else.

Dave Bancroft was one of the players to be elected to the Hall of Fame by the veterans committee during the reign of Frankie Frisch, and so at times, he gets thrown in with some of the other questionable inductees. We should separate him out. Bancroft was a tremendous defensive shortstop. He would study batters and write down their tendencies long before Statcast™ was around to help. They used to call him “Beauty,” because that’s what he would yell every time a pitcher threw a particularly good pitch.

Rabbit Maranville was one of baseball’s great characters… as well as being a terrific shortstop. One of my favorite little facts about him is that he liked catching fly balls off his chest. That is to say, he’d get under the ball, let it hit his chest like it was a soccer ball, and then guide the ball down into his glove. We’ll have to do a Rabbit Maranville post sometime.

Dick Bartell was a loudmouth and a ferocious player—“a snarling chatterbox,” writer Lee Allen called him—people booed him all the time. His nickname was Rowdy Richard and he would routinely (and quite proudly) spike players, call them all sorts of names, try to start fights, etc. But he was one helluva defensive shortstop.

Hey, if you feel like it, I’d love if you’d share this post with your friends!

Other shortstops who are more or less in their league defensively—Roy McMillan (plus-509), Jack Wilson (plus-505), Luis Aparicio (plus-448), Joe Tinker (plus-442) and so on. Mark Belanger (plus-392).

And at the bottom, well, here you go:

Jimmy Rollins, minus-434

Larry Bowa, minus-404

Jose Reyes, minus-346

Leo Cardenas, minus-302

Edgar Renteria, minus-300

Those five kind of stand apart defensively. I hate to see Rollins there, but the numbers are the numbers. Rollins’ range fell off a lot after he turned 30, as tends to happen to most shortstops, but in truth he never had great range. There’s more to defense than just range factor, of course—this is simple, back-of-the-envelope math—and by more advanced numbers, Rollins was a very good defensive shortstop in his prime.

So, there you have it… oh, wait, I forgot someone.

Derek Jeter, minus-1,213 PAA.

Yeah, that’s right. Derek Jeter made TWELVE HUNDRED FEWER PLAYS than the league-average shortstop would be projected to make. There’s nobody else in his universe. That’s so much worse than any other shortstop in baseball history, it’s hard to even compute. Maybe it will make sense when you put together the same list of shortstops as in the above chart:

Career Plays Above Average

Ozzie Smith (1,065)

Luis Aparicio (448)

Robin Yount (331)

Cal Ripken Jr. (90)

Derek Jeter (minus-1,216)

Whew. Look, there are certainly other ways to look at this. Maybe, like, with Rollins, you can look at more advanced metrics like Baseball-Reference’s RField—defensive runs above average

Ozzie Smith (239)

Cal Ripken (181)

Luis Aparicio (149)

Robin Yount (25)

Derek Jeter (minus-253)

OK, that doesn’t help. Look, just say that Derek Jeter was a great hitter. Say he was a great leader. Say that the Yankees were willing to accept his limited range in order to get his exquisite baseball awareness and sure-handedness. But Derek Jeter was a well-below-average defensive shortstop, and no charts or absurd Gold Gloves will change that.

And yes, I blame you, Brandon McCarthy, for making me do all this.

As long as we’re here, though, I will use PAA to show you the top 10 shortstops per nine innings:

Troy Tulowitzki, .46 better than average

Ozzie Smith, .44

Jack Wilson, .42

Dave Bancroft, .42

Rick Burleson, .36

Andrelton Simmons, .34

Dick Bartell, .33

Rafael Furcal, .31

Tim Foli, .30

Rabbit Maranville, .29

I purposely skipped Tulo earlier because I knew this was coming up. He only played 1,268 games at shortstop because of all the injuries, but he really was a defensive dynamo.

In 2007, Tulo barely lost the Rookie of the Year balloting to Ryan Braun. You could sort of understand it—Braun, in 113 games, led the league in slugging and had a 1.004 OPS. The guy mashed.

But Tulo was much better than Braun that year. I mean MUCH better. He was a pretty darned useful offensive player himself, hitting .291/.359/.439 with 104 runs scored and 99 RBIs. But, more than that, his defense was otherworldly. That season, Tulowitzki made 145 more plays than the average shortstop. Almost one per game. Incredible. Impossible.

If Troy Tulowitzki could have stayed healthy, he would have been a Hall of Famer, I think.

Finally: I do want to make special mention of Omar Vizquel, because he comes up so often in such discussions. This will also underscore what I was saying about Ozzie Smith. Omar was unquestionably a dazzling shortstop. He made all sorts of wonderful plays that made your eyes pop out. And he made the barehanded plays like nobody else.

But how PRODUCTIVE a shortstop was Omar Vizquel? See, that’s what separated Ozzie. He was elite at both. Vizquel was not. His range over his entire career was almost exactly league average—he made just 26 Plays Above Average. He did have some very good defensive seasons, like 1998 (26 PAA) and his partial 2003 season (39 PAA in just 64 games), but he also had some mediocre ones. Vizquel never once led the league in assists and only once in putouts and only once in double plays turned. He was so much fun to watch. That keeps him fresh in the memory. But he was not in Ozzie’s stratosphere.

JoeBlogs Week in Review

Monday: Fame 45: Red Ass.

Tuesday: Joe-Pourri!

Thursday: Our baseball preview kicks off: No. 30, Colorado Rockies.

“Can’t make errors if you can’t get to the ball.” *grins at camera, taps head*

As Brent H. Mentions, you can't take these numbers - either the errors on their own, or the range factors, or whatever - on their own. The team and league context matters. Guys like Bancroft and Maranville and Bartell and yes, Ozzie, are naturally going to make more plays per nine because they played in a league context with much lower strikeout rates. And they're going to have more plays above (or below) average depending on how much playing time they got.

Jeter played more games at SS than anybody but Omar, so his counting stats will be higher. But even adjusting for playing time, Jeter still looks bad. His -0.45 PAA/G is more than double anybody else on Joe's list (Reyes, at -0.21).

Jeter also almost exclusively played behind pitching staffs that struck out a lot of batters. The Yankees, in his 20 seasons, averaged 4th in the AL in K's, and only once finished in the bottom half of the league. By my estimates, their penchant for strikeouts meant they allowed about 80 fewer plays than average to be made in the field each year, over 1600 for his career. Not all of those would have been grounders to short, of course, so that doesn't account for all of Jeter's apparent short(stop)comings, but it explains some of it.

Even with that, though, A-Rod was a contemporary of his, and his RF/9 as a SS was exactly league average, this despite also playing behind strikeout-prone pitching staffs (average AL rank: 4.6) for much of the first half of his career.

I think the article in the first edition of the Fielding Bible explained it pretty well: Jeter tended to play shallow, so he was actually pretty good with those slow rollers, above average at turning those into outs. But because of that he conceded...basically everything else. He had a strong enough arm to make that fun throw from deep in the hole 3 or 4 times a year, but he missed what should have been an easy grounder up the middle like once every other game.

The really amazing thing to me is not that he did that, but that for some reason the Yankees allowed him to keep doing it! I guess winning fixes a lot.