Fernando

There was something in the air that night

The stars were bright

Fernando

They were shining there for you and me

For liberty

Fernando

—“Fernando,” by ABBA

There’s a baseball statistic I have been working on called JAR. It stands for “Joy Above Replacement.” For a time, I called it HAR (Happiness Above Replacement) and DAR (Delight Above Replacement), and even FAR.

The last stands for Fernando Above Replacement.

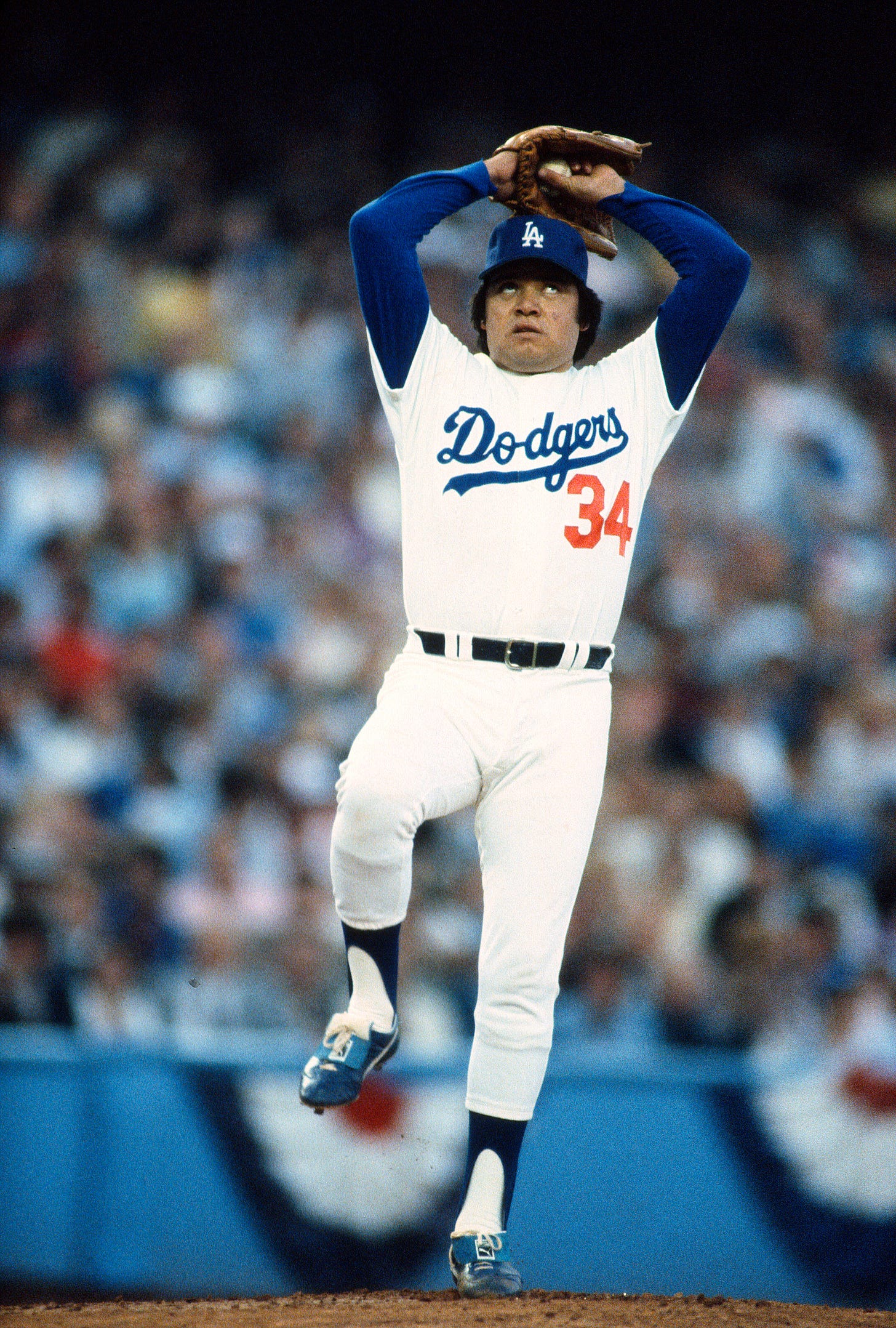

I honestly believe that Fernando Valenzuela, inning for inning, brought more glee, more laughter, more euphoria, more bliss and more happy feelings than any player in baseball history. To watch him pitch was to smile. The watch him hit was to feel a little more alive. To see him unwind his body as only he did—always pausing for an instant to look up to the sky as if he were asking God: “Are you watching this?”—and then uncork that magnificent screwball that had a mind of its own and to watch hitters helpless against its power, all of it took all of us one step closer to heaven.

“Everybody loved him,” his lifelong chronicler, translator and friend, Jaime Jarrín says. “Everybody. But especially women… and especially ladies from 30 years and up. Mothers. Grandmothers. People used to pray for him. They used to go to Mass on the day he was pitching. Baseball had never seen anyone like this before.”

Never before. Never since. Fernando just showed up one September day in 1980, 19 years old; the Dodgers had no intention of calling him up so soon, but he left them no choice. Down in San Antonio, he pitched 35 consecutive scoreless innings. The Dodgers were baseball royalty in 1980, the team of Garvey and Dusty, Lopes and Sutton, Lasorda and the Penguin, and they had all heard about this Mexican phenomenon throwing scoreless innings down in Double-A.

And up comes this kid who, well, let the legendary columnist Jim Murray describe him.

“He doesn’t even look like a major league pitcher,” Murray wrote. “He is, how shall we say it—he is—well, he’s fat, is what he is.”

Fat. Happy. His first time on the mound in Atlanta was nothing special. Ron Cey and Derrel Thomas booted ground balls behind him. He was called for a balk. He got scant mention in the Los Angeles Times as the lone bright spot in a 9-0 defeat. It is worth noting that on the day Fernando Valenzuela made his big-league debut, Mark Fidrych—another wonderful pitcher who is among baseball’s all-time leaders in Joy Above Replacement—was pulled from his scheduled start. His career was at the end.

“That the way it goes,” Rick says in “Casablanca.” “One in, One out.”

His next time out, the Times offered a little more information; they reported that he spoke no English and needed to get all of his instructions from 41-year-old Dominican Manny Mota. They made a wonderful pair, Valenzuela and Mota, separated by 22 years, a lifetime of baseball.

A few days later, manager Tommy Lasorda called for Fernando with runners on first and second and just one out. He got out of the jam. Manny Mota cracked the game-winning pinch-hit for the Dodgers in the 12th.

More details began to emerge. Fernando liked drinking beer. He had learned the screwball from a teammate, right-handed relief pitcher Bobby Castillo, less than a year earlier. He was one of 12 children. The Dodgers had paid $120,000 to Puebla, a Mexican League team, to get him… and Fernando got $20,000 of that.

“I gave the money to my family,” Fernando said.

In all, Fernando Valenzuela pitched 17 2/3 innings in relief that first September, and he did not give up an earned run. There was talk of the Dodgers pushing him to lose a few pounds and get in better shape for the next season.

“Don’t you dare!” Tommy Lasorda boomed.

The next year, after a flurry of injuries to their starters—a longstanding Dodgers tradition—they had Valenzuela start on Opening Day. He was the first pitcher since Lefty Grove to start his first game on Opening Day. He threw 106 glorious pitches against the Astros. He allowed five hits. He allowed no runs. He smiled throughout.

“Did They Tell Him Batting Practice was Over?” The Los Angeles Times headline wondered.

“How did you sleep last night?” reporters breathlessly asked Valenzuela looking for the nerves that had to be there.

“Como un niño,” he said. “Como un ángel.”

Like a kid. Like an angel.

No nerves. No doubts. Nobody could believe he was so young. “They’re going to try to tell me that guy’s 20,” the Angels manager, Jim Fregosi said. “He was 20 when I started playing,”

Fernandomania was on. In his next start, against the Giants, he gave up the first run of his big-league career—a run-scoring single from Enos Cabell—but it was the only run he gave up. Four days later, the Dodgers went to San Diego, Fernando pitched a shutout and added two hits. The 20,000 or so in attendance gave him a standing ovation when it was over.

“I hope he comes back down to earth,” the Astros’ Don Sutton said. “Or they find a higher league for him,”

The Dodgers came home, and about 50,000 fans showed up to watch him pitch. Jaime Jarrín, who had been calling Dodgers games in Spanish since 1959, thought the crowd looked fundamentally different from any he’d ever seen at a big-league game. This was a crowd filled with women, a crowd filled with Latino fans, so many of them Mexican.

“People from Mexico,” he said, “people from other Latin American countries like Ecuador, where I’m from, we didn’t have many baseball idols.… He opened up the sport for us. People who had spent all their lives thinking only about fútbol, Fernando gave them a reason to care about the greatest game, to care about baseball.”

Fernando, of course, pitched a seven-hit shutout for them. And as a bonus, he cracked three hits, raising his season average to .438. A teenage girl raced on the field to kiss him. Jerry Martin, after swinging at least a foot over a pitch, asked the umpire to check the baseball. The former welterweight champion of the world, Carlos Palomino, came to ask Fernando about his training techniques.

“How’s he holding up?” reporters asked Jarrín.

“Wonderfully,” Jaime said. “He’s only now beginning to realize that everyone is asking him the same questions.”

After allowing a run in Montreal, Valenzuela threw his fifth shutout in seven games when the team went to New York. The Mets left 10 runners on base in the game—postgame, they sounded downright jubilant after almost scoring—and they actually loaded the bases with one out in the first inning.

That’s when Fernando persuaded Dave Kingman to hit into the inning-ending double play.

“When he wants to throw a double-play ball, he does,” Lasorda said in wonder after the game. “When he wants to strike out someone, he strikes that someone out. You don’t figure him out.”

Ah, alas, sooner or later, everyone gets figured out, at least a little bit. You can’t do the same magic trick again and again without people eventually getting wise. In that 1981 season—one chopped up by the players’ strike—Valenzuela became the only pitcher in baseball history to win the Cy Young and Rookie of the Year awards in the same season (Paul Skenes might pull off the double this year) and he pitched the Dodgers to their first World Series title in 15 years.

But the mania did die down. Like fires, manias eventually run out of oxygen. Valenzuela was an All-Star in each of the next five seasons, he won 21 games in 1986 and finished second in the Cy Young voting to Mike Scott, but he was no longer front-page news every time he pitched. Hitters learned to lay off the screwball. He had to keep finding new ways to get people out. He was, I suppose, just a little bit more earthbound.

Still, there is this, a trivia question: Can you name the National League pitcher who, over the last 100 years, had the most shutouts by age 25:

(A) Tom Seaver

(B) Don Drysdale

(C) Dizzy Dean

(D) Juan Marichal

(E) Fernando Valenzuela

The answer, of course, is (E), which stands for Excitement and Elation and Excellence and “EEEEEEEE!” which was the sound fans made when they watched him pitch.

In all, Fernando Valenzuela pitched until he was 36 years old, eventually leaving the Dodgers to pitch for the Angels and Orioles and Phillies and Padres and Cardinals. Sometimes he would find a bit of the old magic. Most of the time, he just battled to get one more out. All the while, he still unwound his body, like he was untying himself from a knot, and all the while, in the middle of that windup, he looked to the sky for a little help from above.

Fernando died on Monday. He was 63. He was too young. But any age would have been too young. He was the people’s pitcher, a long-haired, pudgy lefty from Etchohuaquila who became a star and brought baseball fans more Joy Above Replacement than anyone. He made us all believe that if we, too, could just find a screwball, maybe, just maybe, we could strike out the world.

In 1981 I was a young lawyer at the recently opened LA office of the country’s biggest law firm. Of course the first thing the firm did when it opened was buy 4 season tickets to the Dodgers. But most of our clients were back East so virtually every night at around 6 I got a call from the slightly older associate who handled the tickets informing me (as usual) that nobody was using the tickets and did I want to go to the game (we were downtown so it was a short drive to the Stadium). Being single and a huge baseball fan (Orioles) I’d invariably say yes. So I had the privilege to see almost every Fernando start that season. It was magical. He reminded me of Babe Ruth - a superb athlete in a pudgy unathletic body who could not only pitch but was a superb hitter and fielder. What a magical summer! And just about every game I couldn’t help but wonder what Tommy Lasorda thought about his decision to start Dave Goltz instead of Fernando in that one game playoff against the Astros the previous year😂. The only thing remotely similar I experienced was going to see Vida Blue his rookie year facing off against Jim Palmer at old Memorial Stadium. Susan Sarandon, and all of us, must be very sad today.

I know Fernando doesn't have the career numbers to match other Hall of Fame players, but to me, there's no reason to have a Hall of Fame if you can't find room for a player like Fernando. As Joe noted, the impact Fernando had on the sport, and especially in Los Angeles, was massive. At his peak, he was certainly among the all-time greats. That, combined with his cultural importance, should be more than enough.