Fame 49: The Perfectionist

OK, so we’re going to keep it rolling here today with the next name on our countdown of the 50 most famous baseball players of the last 50 years. And as special offer, we’re sending this one out to everybody as a free preview. But from here on out, these will only go to paid subscribers, so hoping you’ll sign up! And as an added incentive, here’s 20% off!

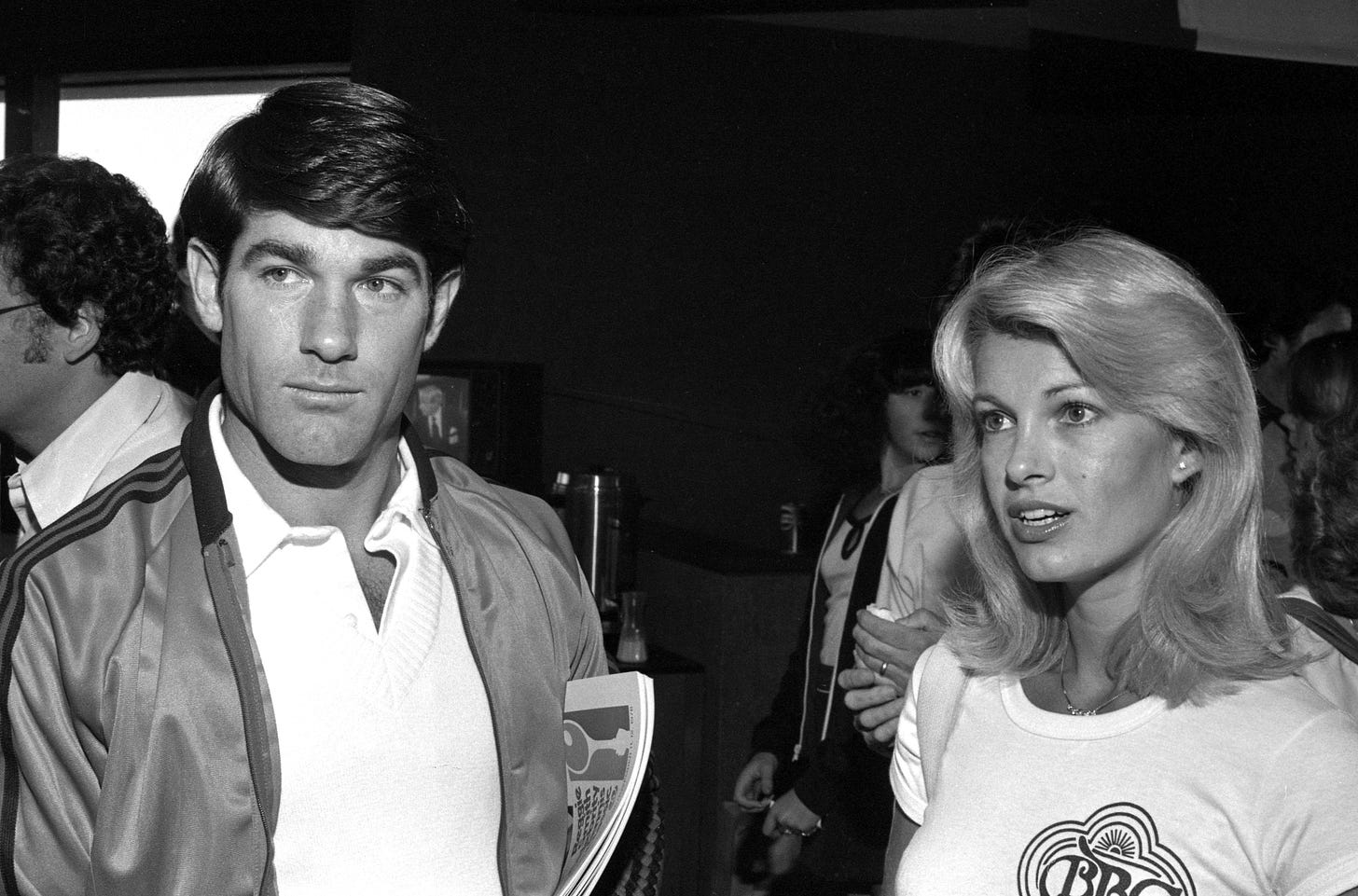

No. 49: Steve Garvey

Where you voted him: 90th overall

My favorite Steve Garvey story comes from when he was at Chamberlain High in Tampa. As you might imagine, if you know a little something about Garvey, he was the ideal high school student. Captain America, they would call him soon enough. He was the star quarterback of the football team (and also kicker), star of the baseball team, winner of the Principal’s Award for all-around excellence, straight-A student, local hero whose name was in the paper pretty much every day.

It wasn’t enough. It was never enough for Steve Garvey; that’s just the way he was wired, the way he is wired, never enough. That’s the impulse that pushed him to superstardom and the impulse, alas, that tore it all down. And so 17-year-old Steve Garvey decided he just had to be in the school’s choir. There was a different sort of fame there, a different kind of respect and admiration and perhaps even love that he could gather by singing, something beyond football and baseball cheers.

His only problem was: He couldn’t sing a lick.

What drives a young man at the top of the world to loudly sing so out of tune that the choir director has no choice but to leave him out of the first performance? Garvey raced into the director’s office with tears streaming down his face; he had never failed before, and he had no idea what to do with the feeling. The director told him that his voice simply wasn’t good enough; perhaps he could accept that he had already been given so many gifts and no one can have everything.

Garvey could not accept that. So what he did was convince the director to let him go to the first performance as a piano mover—while still dressing up as if he were part of the choir—and then Garvey worked on his song by that piano every single day for as long as it took until he earned his way into the choir and sang in the state competition.

I’m not sure that anyone in baseball history has chased fame with the white-hot intensity of Steve Garvey. When he was 7, he became spring training bat boy for the Brooklyn Dodgers. He continued on in that role throughout his childhood, even after the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles.

Being surrounded by Pee Wee Reese and Duke Snider and Frank Howard and Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale and especially Gil Hodges left him romantic about baseball in ways that shaped his entire life. It wasn’t enough to become a baseball star. He desperately needed to become a certain kind of baseball star—a hero, a role model, an icon, a little slice of perfection.

First, he had to be a Dodger. That was non-negotiable. When the Minnesota Twins took him in the third round of the draft out of high school, he never even considered joining them. He went to Michigan State instead, where he became a football starter for legendary coach Duffy Daugherty* and a baseball star for former big leaguer Danny Litwhiler. In his first at-bat on the baseball team, he hit a grand slam into the Red Cedar River. After he hit .376 in the 1968 season, the Dodgers took him in the first round of the draft, and he did not hesitate.

*Garvey so idolized Daugherty than he named his dog Duffy.

Then, he put into motion the most meticulously detailed blueprint to stardom imaginable. Garvey had many limitations as a player. He was not very big (listed at 5-foot-10, 190 pounds), and he was not very fast, and he had a weak and erratic arm. His plate discipline was questionable at best; Garvey hardly ever walked.

But what Garvey had in abundance—as he showed by refusing to get cut from his high school choir—was extraordinary discipline and unyielding will. So, first step to stardom: He would never miss a game. Not ever. From Sept. 3, 1975, through July 1983 (his first season with the San Diego Padres), he played in 1,207 consecutive games. That is still a National League record and probably will be forever.

Second step to stardom: He would get 200 hits per season every year. The number spoke to his ordered mind. He wrote “200” in his glove, and he laid out a detailed plan for getting 200 hits, one that included getting a certain number of bunt hits every month.

Garvey’s hits by year:

1974: 200

1975: 210

1976: 200

1977: 192

1978: 202

1979: 204

1980: 200

His teammates, many of them, despised the 200-hit plan; they thought it selfish and absurd. Garvey once caught them high-fiving each other when one of his carefully timed bunt attempts was turned into an out.

Then, for the most part, teammates never liked Garvey or understood him. The third part of his plan was to be the sort of old-fashioned baseball hero that he imagined as a 7-year-old bat boy. He spent every waking hour signing autographs and visiting hospitals and speaking at banquets and representing charities and doing interviews and appearing on television. He was the proudest square in sports, Mr. Clean, didn’t drink, didn’t smoke, didn’t swear, the handsome prince rebelling against the rebels.

“In the ’60s, everybody was trying to gain awareness,” he told Sports Illustrated. “They were trying to find out who they were.… Now we’re getting back to Americana. I would like to strengthen the country through athletics.”

He really talked like that, and teammates—not all of them, but a lot of them—found it ingratiating and insincere.

“Maybe we’re less mature,” Davey Lopes said. “But the other eight starters look at baseball as a game. Garvey thinks of it more as a business. That’s fine with me, it’s just not my bag.”

“If he wants to go out of his way to be the clean-cut kid, that’s fine, as long as he doesn’t interfere with my style,” Ron Cey added. “Sometimes, he has interfered.”

“He’s a Madison Avenue facade,” Don Sutton said; those two once got into a brawl in the clubhouse.

“He’s so wound up in his image,” an unnamed player said. “A lot of us think it’s phony.… Steve Garvey doesn’t have one friend on this team.”*

*It should be said again: Not all of his teammates felt this way. Jay Johnstone had a great quote about Garvey’s teammates disliking him: “Anybody who has plastic hair is going to have a problem, especially if he shaves with a hammer and chisel and is short. People are naturally going to say things. But with Steve Garvey, the guy just doesn’t change. He may have butter oozing out of his mouth, apple pie in his back pocket and flags on his car, but the guy is the same in the clubhouse as he is out of it. He doesn’t profess to be what he isn’t. Someday, he’ll be President.”

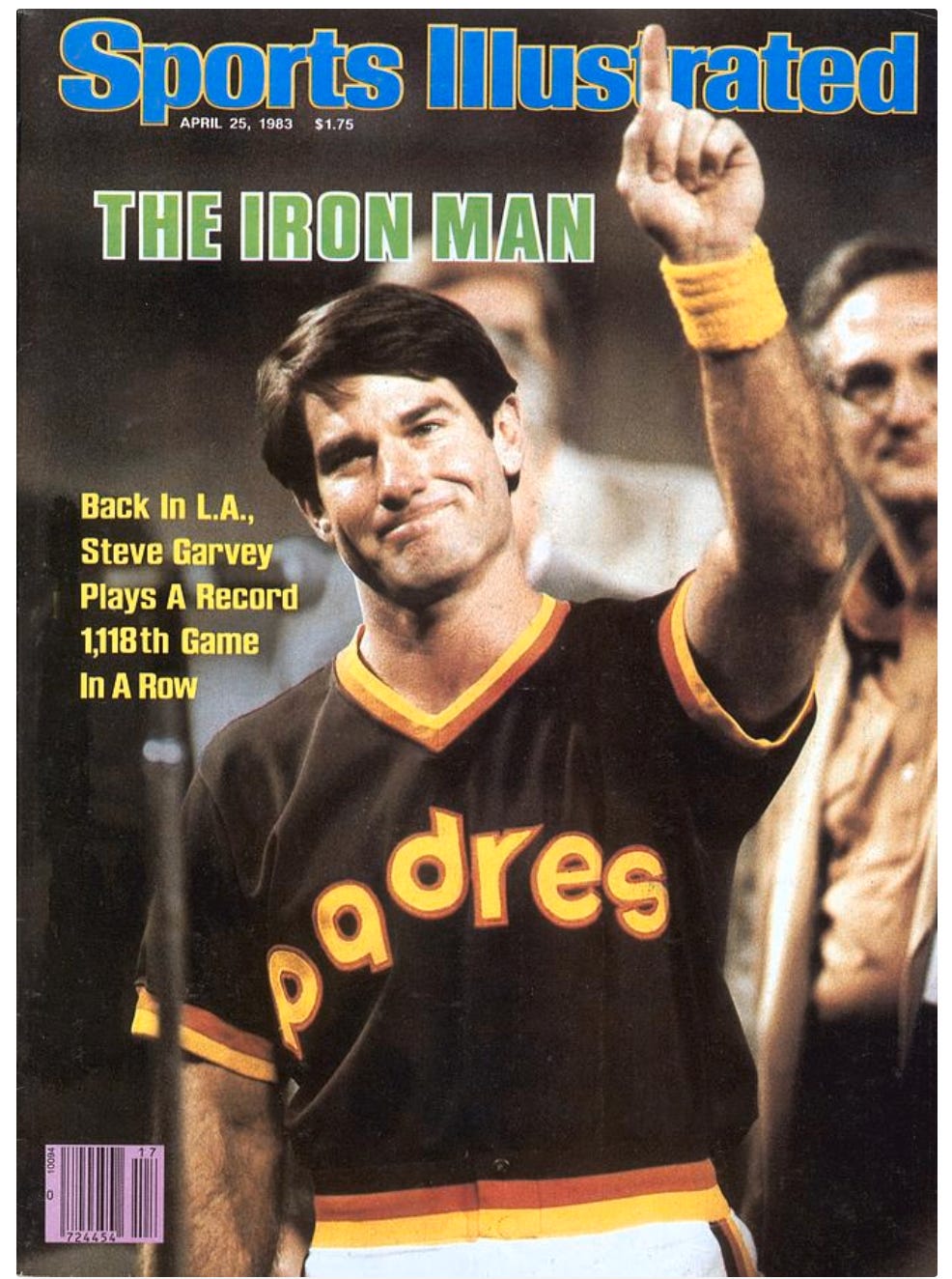

All of this hurt Garvey a lot, but he was on his journey, and if he wasn’t going to let his awful singing keep him from making the choir, he sure wasn’t going to let some teammate sniping prevent him from becoming the most famous good guy in baseball. In 1974, he won the National League MVP award. From 1974 through ’80, he started at first base in every All-Star Game. He drove in 100 runs five times. He was twice the All-Star Game MVP and twice the National League Championship Series MVP. He hit .338 in the postseason.* He was a game show regular, appeared as himself on Fantasy Island, and was on three Sports Illustrated covers. He was called “future Hall of Famer” so many times that after he retired it was the title he would use every time he appeared to sign autographs at card shows.

*In the 1981 World Series, Garvey led the Dodgers in average; he hit .417. But three other Dodgers—Cey, Pedro Guerrero and Steve Yeager—were named co-MVPs.

Garvey’s fall from grace was swift and ugly and can probably be summed up by a joke Pete Rose told me years ago.

“Did you hear about the Breeder’s Cup?” Rose asked me.

“No.”

“I bet on it,” he said. “And Garvey won it.”

If not for the numerous lawsuits that revealed Garvey’s many imperfections—which included numerous paternity claims and testimony from his own kids saying that they didn’t want to see him—Garvey might be in the Hall of Fame. He did get an impressive 41.6% of the vote in his first year on the ballot, and this was after those ugly allegations went public.

But that was the highest percentage he would ever get. I do think the off-the-field stuff hurt him, but also a closer inspection of his career showed that many of the accomplishments that launched him into the stratosphere in the 1970s and 1980s do not hold up all that well. His lifetime on-base percentage is an unimpressive .329, he never slugged .500 in any season, and frankly, 200 hits in a season stopped being a touchstone for greatness somewhere along the way. I think these are the bigger reasons why Garvey is not in Cooperstown.

These days, Garvey is running for Senate in California—he’s the only Republican in the running—and he’s trumpeting his life in baseball, his dedication to doing things right, and his 34-year marriage. He’s an underdog, but that certainly never bothered him. No, the thing that bothered him is best summed up by his former teammate Rick Monday.

“The one thing we know for damn sure,” Monday said, “is that none of us is perfect.”

During the years of paternity suits, a popular bumper sticker in San Diego read, "STEVE GARVEY IS NOT MY PADRE."

Garvey exemplifies a discomfort I have in using modern analytics to judge past careers, for hall of fame purposes.

Let's say you've got a 70-grade center fielder. Everyone tells him, "don't worry about the occasional double, just try to prevent as many singles as you can," so he plays shallow and is one of the absolute best at doing the job he's told to do.

When he retires, someone does an analysis and shows, in fact, the doubles he allowed had a much greater value than singles he prevented and, according to baseruns, this guy was a net negative defensively. His coaches told him which tradeoffs to make, and he excelled; but because his coaches were wrong about the tradeoff, we look back at him as a middling defender. If he'd been told to field the way he would be today, he would have excelled. But they told him to optimize the wrong thing and now he's being punished for optimizing the crap out of it.

Thus, I think is the best Garvey HoF case. Baseball had a set of values and he optimized based on those values enough to earn the 'future hall of famer' moniker. Then, we came up with a different set of values and found him wanting. It feels unfair to change the measure of worth after someone's career is over (at least when it's negative; I'm all for rewarding people who did great things we didn't realize were great at the time).

I think about this at an abstract level; I personally don't care about Garvey.