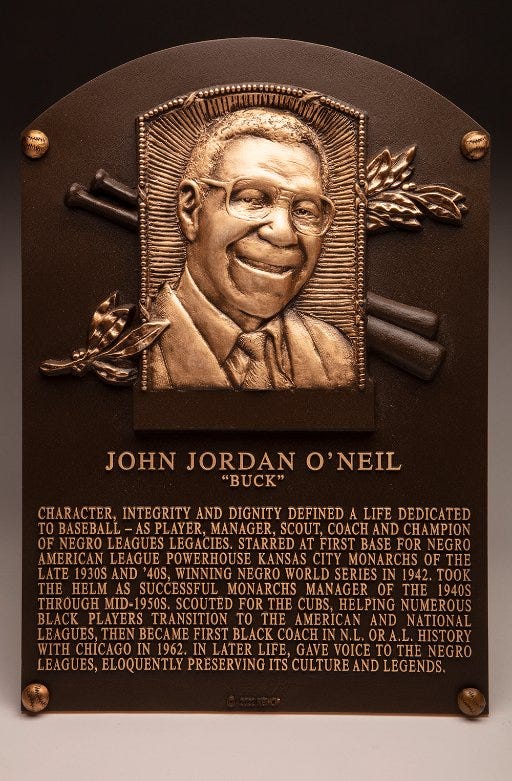

Buck

COOPERSTOWN, N.Y. — “Somebody,” Buck O’Neil said to me, as we sat over the remainders of lunch at the Peachtree restaurant on 18th and Vine, “somebody should write about the Negro leagues the way they really were.”

“Somebody,” he said to me, “should write about how much fun it was. How good we were. We could play, man!”

“Everybody,” he said, “talks about the bad stuff. And that’s all they want to talk about. We know about the bad stuff. We know about segregation. We know about hatred. We know the sad stories. But the Negro leagues weren’t sad. We were playing baseball. In fact, we were playing some of the best baseball that has ever been played.”

“Somebody,” he said, “should write about the way it really was.”

Buck kept saying “somebody.”

And I was the only one there.

That lunch, after too many stops and starts to count, led to me spending the summer of 2005 traveling the country with Buck. That led to the book The Soul of Baseball. That led to the incredible journey that has been my lucky life.

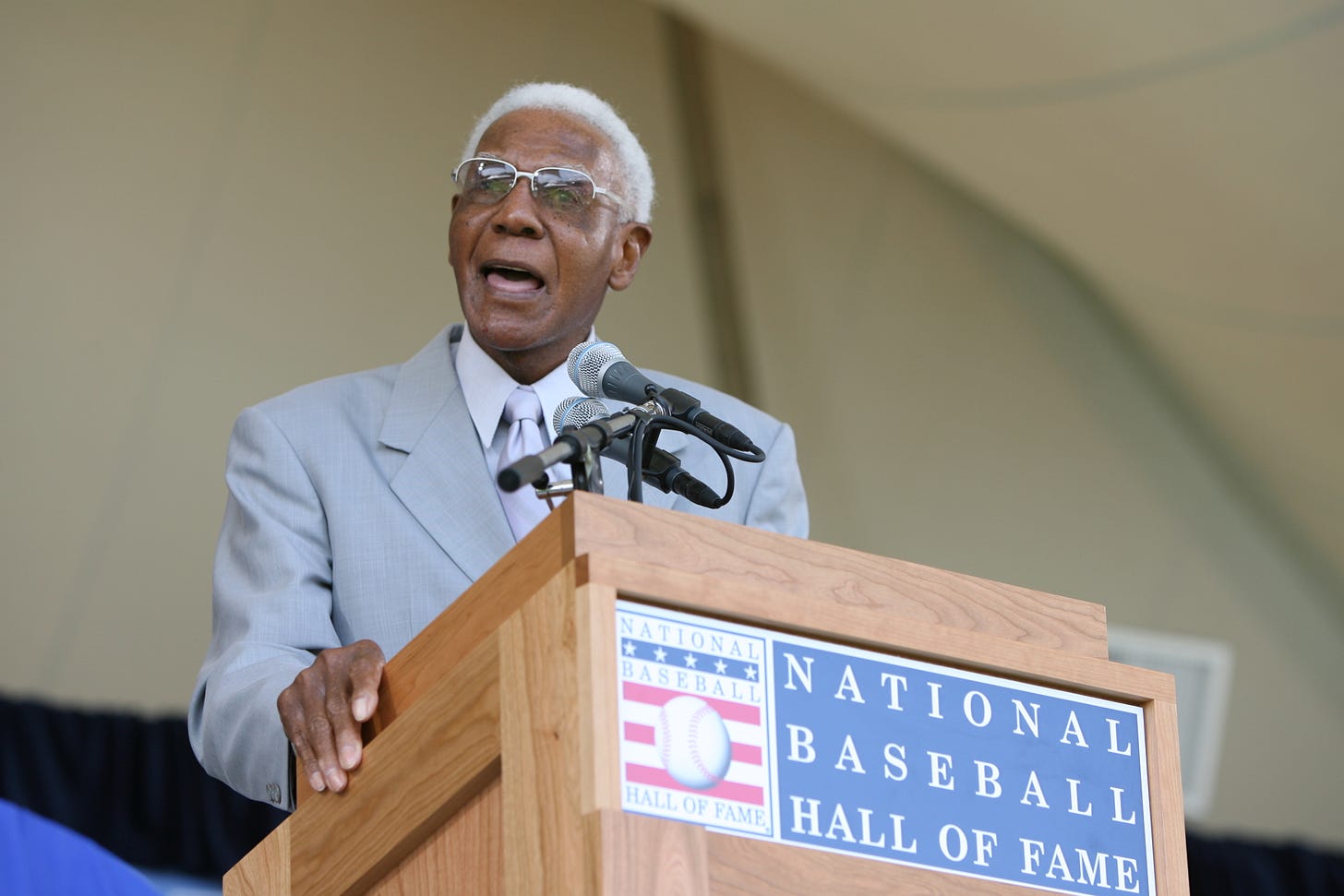

Even now — some 20 years later, as Buck O’Neil is inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame — I cannot tell you exactly why Buck chose me. I cannot tell you what he saw in me. I was a 30-something newspaper columnist in Kansas City, a new father, an author of exactly zero books, and, as Buck often reminded me, “a white boy.”

“What’s better, Gates or Arthur Bryant’s?” he once asked me about Kansas City’s two most famous barbecue brands.

“Bryant’s,” I said.

“Aw, what do you know? You’re just a white boy,” he said.

All I can say is that Buck, well, he was a natural scout. He scouted Lou Brock, Lee Smith and Joe Carter. I guess, he scouted me.

Lynn Novick met Buck O’Neil shortly after she started at Florentine Films, working with Ken Burns on “The Civil War” documentary. Ken and Lynn’s next project was to tell a different kind of baseball story — one that would show how the game’s history and American history intertwine and interweave and mirror each other. This meant telling the story of the Negro leagues as it had never been told before.

But how? Lynn was responsible for digging into the Negro leagues, and it wasn’t easy in those days. There were only a handful of books. Many of the greatest Negro leaguers — Paige, Gibson, Charleston, Cool Papa — were gone. Perhaps the most famous Negro leagues narrative was the movie “Bingo Long and the Traveling All-Stars,” a film Buck absolutely loathed. “It wasn’t like that,” he used to say, with a rare edge in his voice. “We were no minstrel show.”

Someone told Lynn that she might want to talk with Buck O’Neil. She’d never heard of Buck, but she called, and he seemed amenable, so she showed up at his door in Kansas City with a camera crew behind her. She had absolutely no expectations; she just hoped that he would have some interesting memories.

And what followed was an interview unlike any she has had in her entire life.

“It must have been hard playing in the Negro leagues,” she said to him at one point.

He looked at her with amusement.

“No, it wasn’t hard,” he said. “It was wonderful.”

It was wonderful. There was Buck O’Neil in three words. Lynn looked at him in astonishment. Buck was the grandson of enslaved people. He was not allowed to attend Sarasota High School. He was never given a chance to see if he was good enough to play in the major leagues — and he was good enough. He was never allowed to manage in the major leagues — and I have no doubt he would have been an extraordinary manager.

He drank from separate water fountains and was turned away from white hotels and was forced to eat in the kitchens of restaurants that would even allow him in. He saw crosses burned and children spit at and once walked into a crowd of white sheets when he confused a ballpark with a KKK rally.

“It was wonderful,” he said.

And he talked about all the wonderful things, the wonderful players, the wonderful games. He told her stories, incredible stories, about Satchel Paige, about Josh Gibson, about Cool Papa Bell. He told her about walking into the Streets Hotel in Kansas City or the Evans Hotel in Chicago or the Woodside Hotel in New York and being treated like a star, and running into Cab Calloway or Count Basie or Ella Fitzgerald.

He told her about the three times he heard a different crack of the bat.

The first time he heard the sound, he was a kid standing outside the fence during spring training in Sarasota, and he climbed a ladder, and looked, and saw a ballplayer with a barrel chest, skinny legs. That was Babe Ruth.

The second time he heard the sound, he was a ballplayer himself, 1938, playing for the Kansas City Monarchs, and he was in the clubhouse in Washington getting dressed, and as soon as he heard it, he raced on the field wearing whatever he happened to have on. That was Josh Gibson.

The third time he heard the sound, he was a scout at Royals Stadium, and a powerful force was taking a few batting practice swings, and the sound exploded again and again and again, every time he connected. That was Bo Jackson.

For Lynn, it was mesmerizing and awe-inspiring and thrilling. When “Baseball” came out, it had any number of eloquent characters, historians, musicians, some of the best ballplayers who ever lived. But all of them were supporting characters to John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil, who in his own distinctive way captured not only the spirit of the Negro leagues, but of baseball, too.

Hey, if you feel like it, I’d love if you’d share this post with your friends!

After it came out, Buck’s life would change. For years, he had been largely ignored — people had learned that the story of African-American baseball had begun when Jackie Robinson crossed the line, and they weren’t interested in hearing any more. But after “Baseball,” people began listening to him. People began asking him to tell more stories. He wrote a book. He appeared on “Letterman.” He traveled the country.

Lynn Novick was with us in Cooperstown this weekend.

So was her son. His name is John Jordan.

Bob Kendrick grew up in a small town in Georgia called Crawfordville. He loved baseball — Henry Aaron was his hero — but basketball was his thing. He went to Park College in Kansas City on a basketball scholarship. Not long after, he began working in the promotions department at The Kansas City Star.

In 1994, he decided to volunteer and help out a group of people at the regally named “Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.”

It wasn’t a museum then. It was an office space. A few former ballplayers — Buck O'Neil prominent among them — were taking turns paying the rent. The very few Negro leagues artifacts they had were in a desk drawer. If someone would have walked in and asked, “Wait, where’s the museum?” the person in the office would have opened the drawer and said, “Your tour begins and ends here.”

But nobody was allowed into the office.

The first time Bob met Buck, he was mesmerized. Of course he was. They were different men, Bob and Buck, but with the same spirit inside. Buck had this big idea in mind — to build a real-life Negro Leagues Baseball Museum that people would visit to learn the story of Black baseball before Jackie Robinson.

And Bob had ideas. Big ideas. He signed on. He loved the story that much. He loved Buck that much.

Together, and with some other dreamers, they built the museum there on 18th and Vine, just around the corner from the Paseo YMCA, where Rube Foster himself had founded the Negro leagues.

Buck died in 2006. In the 16 years since, Bob — my friend, my brother — has become the living embodiment of Buck O’Neil. He carries around Buck’s kindness, his grace, his style (Buck was the sharpest dresser I ever knew; Bob isn’t far behind) and his devotion to telling the story.

As we walked around the Hall of Fame, a man walked up to Bob and said, “Mr. O’Neil, could you sign this baseball?” It was an awkward situation. But it wasn’t, because Bob put his hand on the man’s shoulder and said a few kind words about Buck and about the Negro leagues and about being so thankful for this weekend.

It was uncanny to me how much Bob sounded like Buck O’Neil.

I’ve never solved the mystery of how Buck O’Neil did it, how he vanquished his bitterness and kept his faith in people and saw the good in the world. I supposed that trying to figure that out is like trying to unravel the mystery of how Shakespeare wrote Othello, King Lear and Macbeth in quick succession, or how Dolly Parton wrote “Jolene” and “I Will Always Love You” on the same night or how Barry Sanders found open field amid a mass of tacklers. It’s all but impossible to comprehend genius.

And Buck was a genius — a genius at optimism and hope and his faith in humanity.

“What a jerk,” I said about that guy at the Astros game who stole a ball from a kid.

“Don’t be so hard on him,” Buck said. “He might have a kid of his own at home.”

And I pondered that.

“Wait a minute,” I said. “If he has a kid of his own, why didn’t he bring the kid to the ballgame?”

Buck didn’t hesitate: “Maybe his kid is sick.”

And I knew I would never, ever beat Buck O’Neil at this game.

I’ve told the story many times about that day in 2006 when Buck O’Neil did not get into the Hall of Fame. Seventeen Negro leagues players and executives and contributors were elected. But Buck fell short. We were sitting in an office upstairs in the museum, and Bob walked in with a look of death on his face. “Buck,” he said, “we didn’t get enough votes.”

And Buck, quickly, instinctively, said, “Well, that’s the way the cookie crumbles.”

I have thought about that moment countless times over the last 16 years … and even more, I’ve thought about how, a few beats later, he asked me who would speak on behalf of the 17 who got in. I shrugged — in that moment, I felt so angry and discouraged that, shamefully, I didn’t care one bit about the 17 who got in, even though it was a monumental step forward in keeping alive the memory of the Negro leagues.

But I lost sight of that because of how sad and furious I was for my friend.

Buck — he just never lost sight of what matters.

“I wonder if they’ll ask me to speak,” he said.

“You’d do that?” I asked.

“Of course,” he said. “Think about this, son. What is my life about?”

That’s what I think about today. Buck’s life was about baseball. And his life was about heart. His life was about music and faith and having dessert after every meal. His life was about shooting his age in golf (which he did just about every age between 75 and 94) and getting on the airplane first and driving that big Cadillac he loves so much (Mercedes once gave him a car, but he couldn’t figure out how to turn it on).

If Buck saw a stranger, he would ask: “Do you remember your first baseball game?”

If Buck saw a kid with a glove, he would take the ball and tell them to run out a ways so he could throw it to them.

If Buck saw a person with an interesting dish in a restaurant, he would say: “What’s that? That looks really good. I might have to get that.”

Buck’s life was about hugs and nicknames (he called our oldest daughter “Sunshine” and our youngest “New One”) and checking out young ballplayers to see if they had what it takes. Buck’s life was about telling Satchel Paige stories, so many Satchel Paige stories …

One time, Satchel was pitching against a white all-star team, and a big lug of guy stepped to the plate, and on the first pitch hit a titanic home fun over the leftfield wall.

“Nancy!” Satchel yelled at Buck — he called Buck “Nancy” for a reason you probably know — “Nancy, come here!”

Buck walked over. Satchel leaned his head toward the guy running around the bases.

“Who dat?” Satchel asked.

Buck shook his head. “Satchel,” he said. “That’s Ralph Kiner. He’s led the National League in home runs the last two or three years.”

“OK,” Satchel said. “Nancy, next time he comes up, you tell me.”

The next time Kiner came up, Satchel Paige struck him out on three pitches.

More than anything, though, Buck’s life was about keeping a memory alive. He spoke in Cooperstown 16 years ago on behalf of the 17.

“People always say to me, ‘Buck, I know you hate people for what they did to you or what they did to your folks,’” he told the crowd that day. “I said, ‘No, man. I never learned to hate.’ I hate cancer. Cancer killed my mother. My wife died 10 years ago of cancer (I’m single, ladies!). I hate AIDS. A good friend of mine died of AIDS three months ago.

“But I can’t hate a human being, because my God never made anything ugly. Now, you can be ugly if you want to, boy. But God didn’t make you that way.”

And then he asked everybody to hold hands. And they did. He asked everybody if they could sing. “Sing after me,” he said. And they sang after him:

The greatest thing/in all my life/is loving you

The greatest thing/in all my life/is loving you

The greatest thing/in all my life/is loving you

The greatest thing/in all my life/is loving you

It was beautiful. It was larger than baseball, more than words, it was pure love on display. See, that’s what Buck’s life was really about. Love.

“Thank you,” Buck finished, and then his last words on the public stage. “I could talk to you for 10 minutes longer. But I’ve got to go to the bathroom.”

Congratulations to you Joe, this had to be a happy, bittersweet day for you. It’s funny - like a lot of us I tend to key on the stats Of the older players, or even some of the ones I saw play like Oliva and Kaat. But I really don’t care about Buck’s numbers, because you have shown us through your writing the true essence of a Hall of Fame man. And I sincerely thank you for that

Joe, I could never get tired of you writing about Buck. Even when it's the same stories I've heard before I could never get tired of them. Like watching Casablanca or listening to Abbey Road, it just could never get old. What a great day for baseball and the nation.